![]()

Interpretive Center offers tours of 100-year-old, fully-restored building

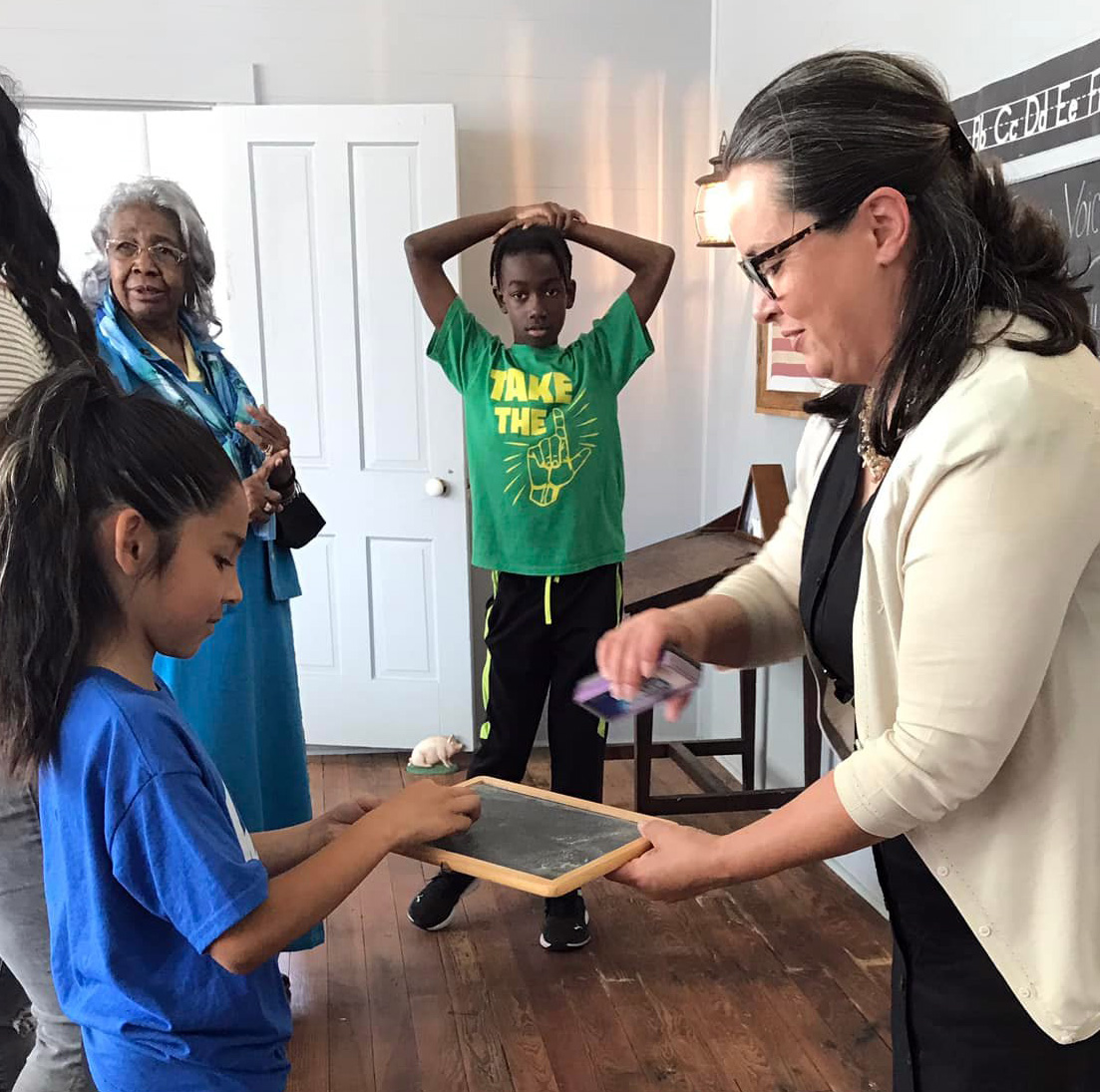

Cindi Ericson gave the child a small slate and a piece of chalk and asked her to write her name. Writing your name with chalk – such a small thing, but the child’s smile was big, and so was Ericson’s. Saturday was her first day to welcome people to the Columbia Rosenwald School as a volunteer.

Nationwide, the Columbia Rosenwald School is the only fully restored school that is open to the public as an interpretive center. Other Rosenwald schools have been saved, restored even, but they are in use as barbershops, community centers or photo studios. Only in West Columbia can you step through the door and see a Rosenwald school as it was in 1921.

A Rosenwald School was a novel approach to educating black children in the rural south. In the early 1900s, schools did not welcome black students. Black children, if they had any education, learned how to read in someone’s home or at church. Booker T. Washington, president of the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, became passionate about changing this. Washington found an ally in Julius Rosenwald, the president and CEO of Sears Roebuck and Co.

With Rosenwald’s money and Washington’s ideas, the pair revolutionized education in the south. Building designs considered natural “lighting, ventilation, heating, sanitation, instructional needs and aesthetics – all to create a positive, orderly and healthy environment for learning. “(National Trust for Historic Preservation)

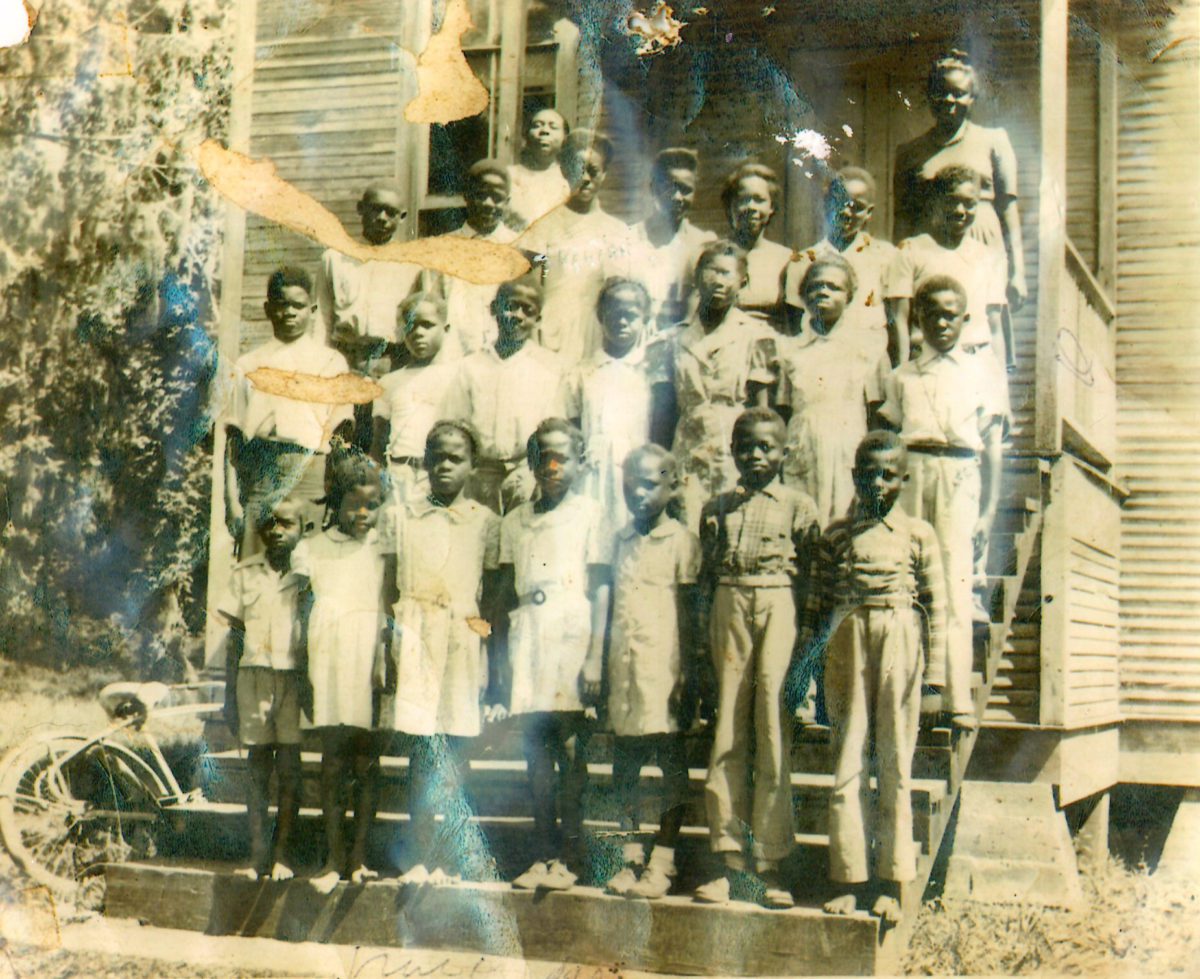

Between 1912 and 1932, nearly 5,000 schools were built, including this one in West Columbia. Originally the school was built along the banks of Varner Creek near East Columbia. In 1949, the Rosenwald students began attending school at Charlie Brown in West Columbia, and the building was closed. Eventually James Phillips III and Alex Weems bought the building, and it was moved to a pasture and began a new life as a hay barn.

In 2001, the National Trust for Historic Preservation classified all Rosenwald Schools as “Endangered Historical Sites”. About the same time, Columbia Historical Museum board member Morris Richardson recognized the old building off Highway 35 as a Rosenwald School and advocated its restoration. The idea quickly gained traction.

Eventually, the building was donated to the museum, and the City of West Columbia gave permission to move the school onto a city park just behind the museum. Work to restore the school began. In 2009, the museum received a $50,000 grant from Lowe’s and the National Trust. Restoration work was quickly completed. The building was opened to the public on Oct. 24, 2009, with music, dignitaries and several alumni.

Twenty years later, the museum is still caring for the Rosenwald School. Bill Womack ensures the original floors are preserved with Tung oil, and Flem Rogers washes the exterior to keep the paint clean and white. A new generation of volunteers is being trained to educate visitors about this national treasure in West Columbia, and Saturday, Columbia Rosenwald alum Dorothy McKinney, now in her 90s, visited her old school house and watched Ericson teach a little girl how to write her name in chalk on a slate.

The Columbia Rosenwald School was originally located near Varner Creek and East Columbia.