![]()

By Tracy Gupton

Death claimed the life of Stephen Fuller Austin, the man known as “The Father of Texas,” on this date 187 years ago. Pneumonia was the villain. The same malady that took his father from him before Moses Austin could see his dream of colonizing the eastern portion of Mexico come true.

The younger Austin died near Columbia at the age of 43 two days after Christmas on December 27, 1836.

Former West Columbia High School teacher and coach James “Deacon” Creighton wrote of Stephen F. Austin’s death: “Christmas Day of 1836 dawned pleasant and balmy. All over Texas, especially along the Brazos, thousands of Texans looked forward to their first Christmas as an independent Republic. Only in Columbia, in the clapboard house of George B. McKinstry, located near where the old Arnold No. 1 oil well now stands, had the bell begun to toll. There Stephen F. Austin lay ill.”

This description of Austin’s demise comes from Creighton’s book A Narrative History of Brazoria County, Texas (Brazoria County Historical Commission, 1975, Texian Press, Waco, Texas). “In the early hours of the warm holiday, the sun had brought Austin some relief, but by ten o’clock a cold norther blew in and Austin’s condition grew rapidly worse. By the morning of December 27 it became apparent that Austin’s case was hopeless. Dr. Levi Jones, brother of Anson Jones (a Brazoria physician who served early Texas as a congressman, secretary of state and the fourth president of the Republic), applied a poultice to Austin’s chest. And Austin said, ‘Now I shall sleep.’

“And though, like (his father) Moses, Austin was to be denied the privilege of entering the promised land—the recognition by the United States of Texas’ independence—still he was to have his own Mount Nebo,” Creighton wrote. “Raising himself on his elbow, Austin whispered in his delirium: “Texas recognized. Archer told me so. Did you see it in the papers?”

Creighton wrote that these were the final words uttered by Stephen F. Austin. “By half past noon the man to whom Texas owes its greatness more than to anyone else breathed his last.”

The Stephen F. Austin Statue is located near Angleton off of Highway 288

Sam Houston, who had defeated Stephen F. Austin in the 1836 election and was sworn in at Columbia as the first president of the Republic of Texas, issued a mournful proclamation when news of Austin’s death reached him: “The Father of Texas is no more! The first pioneer of the wilderness has departed!”

H.W. Brands wrote in his historical book on Texas, Lone Star Nation, “If Houston remained ambivalent about Austin, if anything persisted of the scorn he had felt for the empresario, he cast such feeling aside in the face of death.”

In Lone Star Nation (Doubleday, 2004, New York, New York), Brands wrote that Sam Houston instructed, “As a testimony of respect to his high standing, undeviating moral rectitude, and as a mark of the nation’s gratitude for his untiring zeal and invaluable service, all officers civil and military are required to wear crape on the right arm for the space of thirty days. Garrisons would fire salutes of twenty-three guns, one for each Texas county, and would hang black for the ‘illustrious deceased.’”

James L. Haley wrote in his book, Passionate Nation: The Epic History of Texas (Free Press, 2006, New York, New York), “Columbia’s resources were being overwhelmed by the gathering government” in October of 1836, “and the only lodging Austin could find was the loosely clapboarded shed room in the cabin of Judge George McKinstry.

“From this drafty bedroom office, fitted with neither stove nor fireplace, Austin took a cold that soon deepened into the death grip of pneumonia when a powerful norther ripped through the town in mid-December,” Haley wrote. “Closely tended, he was bedded on a fireside pallet in the main room of McKinstry’s house. Two days after Christmas he seemed to rally and asked for tea. He napped fitfully” before passing away shortly after noon on December 27, 1836.

Haley wrote that “the Texans that grumbled and mistrusted and ignored him in life gave him all the pomp in death that their rude circumstances could muster. Government officials wore black armbands for a month, cannons boomed slow-interval twenty-three-gun salutes, and the Yellow Stone, which had stood by Texas during the revolution, conveyed his body, with Houston as part of the honor guard, for burial at the family compound at Peach Point.”

After independence had been won from Mexico, Stephen F. Austin was defeated for the new republic’s presidency by General Sam Houston, leader of the victorious Texians Army at the Battle of San Jacinto. President Houston appointed Austin secretary of state. Working countless hours on cold winter days in the drafty capitol building in Columbia also contributed to Austin’s failing health.

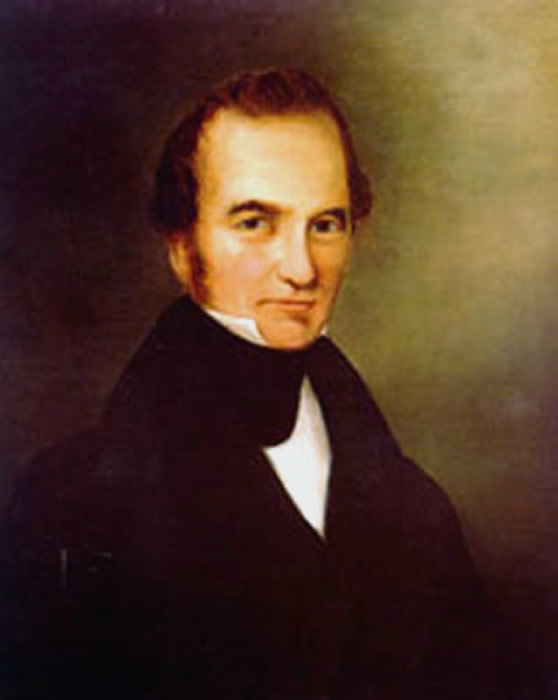

A color portrait of “The Father of Texas,” Stephen Fuller Austin

Creighton, who was a teacher in West Columbia in the early portion of the twentieth century and lived in Corpus Christi while researching and writing his history of Brazoria County, said, “For two days Austin’s remains lay in state” in Columbia. “Then on December 29 at Columbia (now West Columbia) the funeral cortege formed to accompany the body of Austin along the two-mile road to Bell’s Landing (present day East Columbia) on the Brazos. There the steamboat Yellowstone waited to carry the body to Peach Point, home of Austin’s brother-in-law, James F. Perry.

“In the long procession that formed at Columbia were all the members of the government, headed by President Houston, officers of the army and navy, and a great outpouring of citizens,” wrote Creighton. “At Peach Point (in present day Jones Creek), a detachment of the First Regiment of Texas Infantry under Captain Martin K. Snell paid Austin his final military honors.”

Creighton wrote that the town of Columbia and Brazoria County can look back on the year 1836 with great pride when Columbia “reached the apex of historical significance” by becoming the first capital of the Republic of Texas. To think that the two greatest men in early Texas history—Stephen F. Austin and Sam Houston—were living here and running the new government is almost beyond belief.

The following year, in 1837, the capitol was relocated to the new city named after the republic’s first president, Sam Houston, and later moved again to the city named for “The Father of Texas” when Austin became the capital of Texas. But for a brief shining moment in Texas history, West Columbia and East Columbia played a vital role in the Lone Star State’s beginning.

Photo by Tracy Gupton

Stephen F. Austin, “The Father of Texas,” died on this day, December 27th, 187 years ago at this site in the oil fields off of Highway 36 just outside the West Columbia city limits. A state historical marker was placed at the base of this old tree in 1936, 100 years after Austin’s passing at the age of 43. He died in the home of Brazoria County Chief Justice George B. McKinstry of pneumonia two days after Christmas in 1836. McKinstry fought in the Battle of Velasco in 1829 and built his small house on this site in 1830.