![]()

By Tracy Gupton

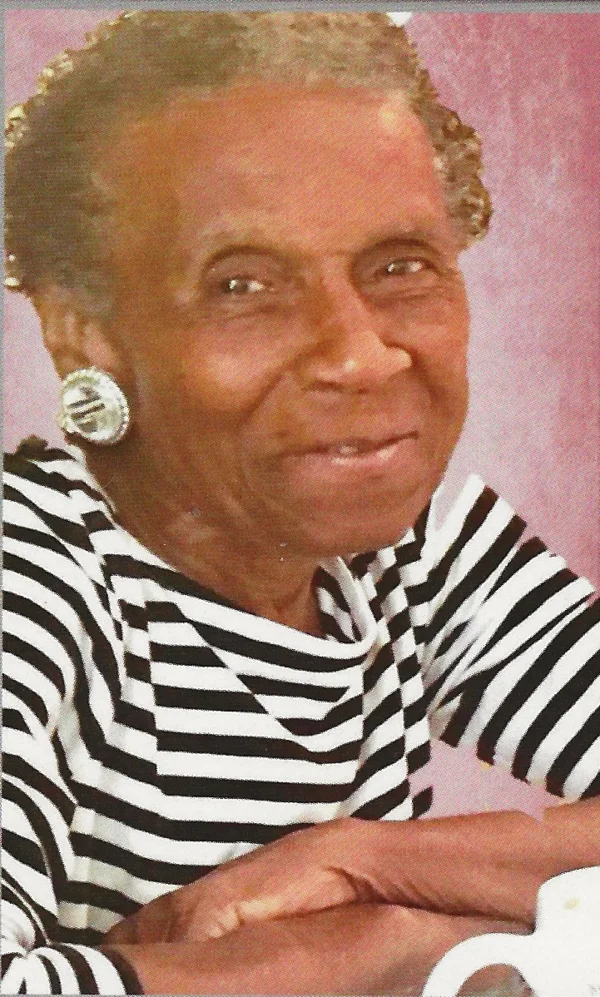

There was not a single seat left vacant at this past Saturday’s funeral service at Blue Run Baptist Church in West Columbia. Some mourners stood along the walls to experience the memorial for lifetime East Columbia resident Essie Mae Diggs Tolbert. Her 88 years of living and enjoying life came to an end on December 16, 2024, just nine days before Christmas. Pastors Charles Jones and Corey Thomas heralded Essie Mae’s long life in shining a light on the large crowd that came together Saturday morning, emphasizing the fact that so many people loved her and cherished their individual relationships with their mother, grandmother, great-grandmother, sister, sister-in-law, aunt, cousin or friend.

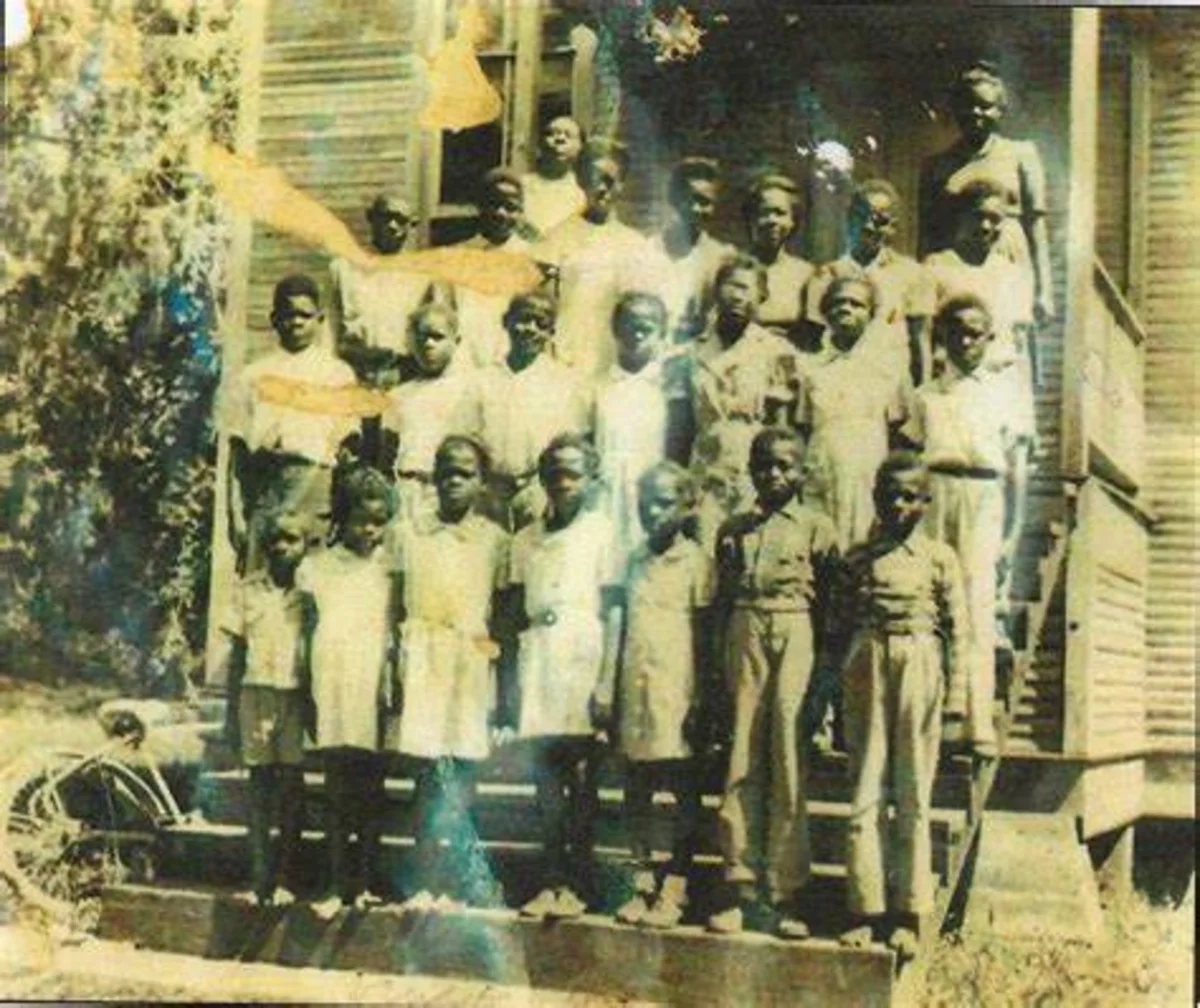

Essie Mae Diggs’ life began in East Columbia July 6, 1936, when she was born the daughter of Maxie Diggs Sr. and Ella Mae Diggs. In her childhood days she attended the Rosenwald School for Black children in East Columbia with her brothers Maxie Diggs Jr., Leroy Diggs, Milton Diggs, Gylum Diggs and Alphonse Diggs, and sisters Lula and Loretta Diggs. The Rosenwald School closed its doors for good in 1948 when Essie Mae Diggs was 12 years old. From that point forward Black children of East Columbia and West Columbia attended school at the Charlie Brown School in West Columbia until racial segregation ceased in the mid-1960s.

A retiree from the Sweetbriar Development Center in West Columbia, Essie Mae and her husband, the late Harold Tolbert Sr., were the parents of seven children. The expansion of their family resulted in Essie Mae being blessed with 21 grandchildren, 40 great-grandchildren and 11 great-great-grandchildren. Trial integration in the Columbia-Brazoria School District during the 1966-67 school year placed Harold Tolbert Jr. and his cousin, Margo Diggs, in Joyce Lester’s fourth grade classroom at West Columbia Elementary School with me, Tracy Gupton. From the time I was in first grade through third grade, all of the Black children attended the Charlie Brown School while all of the white and Hispanic young children went to school at West Columbia Elementary.

Harold Tolbert Jr. and his cousin, Herbert Cotton, who was in my wife Peggy Hall Gupton’s fourth grade classroom with their teacher Dahlia Askew during that 1966-67 school year when the majority of Black students were still attending the Charlie Brown School, were both in the same sixth grade classroom with me in 1968-69. The 1967-68 school year in West Columbia and Brazoria was the first year the local school system was totally integrated. That year the Charlie Brown School became the intermediate school in West Columbia for all fifth and sixth graders, regardless of their race.

My friendship with Harold Tolbert Jr. has lasted the test of time and now, as we both approach our 68th birthdays in 2025, we remain the best of friends. Harold stood up with me as a groomsman at mine and Peggy’s wedding nearly 45 years ago, and I was honored to be asked by Harold to be his best man when my fellow 1975 Columbia High School graduate took Rhonda Bonner’s hand in marriage. His mother Essie was a widow for more than 30 years so when I confided to Harold Friday at his mother’s viewing at Dixon Funeral Home in Brazoria that I envied him having his Mom for so long (my own mother passed away at age 70 in 1996), we agreed that Essie’s life longevity was sadly balanced by the fact that Harold’s father died at the young age of 57. Harold Tolbert Sr. grew up in Old Ocean near Sweeny, Texas, so he did not attend the Rosenwald School in East Columbia with the Diggs children.

The East Columbia Rosenwald School opened in 1921 for the sole purpose of providing Black children of the area a proper place to be educated. Today, the one-room schoolhouse sits on the lot behind the Columbia Historical Museum in West Columbia. In 1999, former Charlie Brown High School Coach and teacher Morris Richardson Sr. informed Columbia Historical Museum board members that the rundown old building being used as a hay barn in East Columbia was originally a Rosenwald School.

Coach Richardson, who had retired as a Sweeny High School football coach, told the local museum board that he had taught at a Rosenwald School in Luling, Texas, before coming to West Columbia to teach and coach football and basketball at the Charlie Brown School. He told them this “hay barn” should be rescued and restored. And the museum board did just that. Spearheaded by Emma Womack and her son, Bill Womack, and Morris and Lois Richardson (both retired school teachers), Jimmy Phillips’ old hay barn was purchased and eventually moved to the middle of downtown West Columbia. After being refurbished and restored to an appearance very similar to what the East Columbia Rosenwald School most likely originally looked like, it was opened for public tours in October of 2009.

Current Columbia Historical Museum Board President Naomi Smith, a retired school teacher herself, thoroughly enjoys giving tours of the Rosenwald School and encourages all area citizens to take the time to visit the museum at 247 East Brazos Avenue in West Columbia and ask to be given a tour of the Rosenwald School behind the museum at the intersection of Clay and Broad streets. The museum is open every Thursday, Friday and Saturday from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m.

The story on the Rosenwald School in West Columbia that appears inside the 2024 btel Brazoria County regional telephone directory states that, “The ‘colored schools’ were often in railcars, abandoned buildings, and even hay barns. They had few amenities other than makeshift desks and benches. Many communities refused to provide education (to Black children) at all. Those (Black) adults who could read and write then taught in churches, on porches and in lodge buildings.”

The Rosenwald Fund, named for former Sears and Roebuck Corporation CEO Julius Rosenwald, was formed in 1912 through a partnership between Rosenwald and former slave Booker T. Washington who was the president of Tuskegee Institute at the time. The story in the btel phone book states that one of every five rural schools built in the South for Black children existed because of the Rosenwald Fund. The former East Columbia Rosenwald School was “one of 533 built in Texas and one of the five built in Brazoria County. It’s the only school left standing in Brazoria County and is one of only five remaining in Texas today.”

Naomi Smith says that the Rosenwald School behind the Columbia Historical Museum is the only one currently used as an interpretive center with period desks, the original teacher’s chair, and a replica of what was used as a desk for the teacher. She said that East Columbia’s school was a one teacher school.

She said the land where all of the Rosenwald Schools in Brazoria County were located was donated by Charlie Brown, an ex-slave who never learned to read or write himself but wanted all Black children to be offered the luxury of being educated. Charlie Brown, who the former school for Black children in West Columbia was named for, “amassed a fortune in land and money,” according to the story in the btel phone book. When he died in 1921, the year the East Columbia Rosenwald School first opened its doors to young Black students, Charlie Brown was the fifth wealthiest man in Texas.

Today the school is a very valuable addition to Columbia Historical Museum and is open for tours, meetings, and community events.