![]()

By Beth Griggs

The twin cities of Columbia and Marion were laid out in 1826 by Josiah H. Bell, on a part of the original land grant he received from the government of Mexico. Josiah H. Bell was a longtime associate and personal friend of Stephen F. Austin, and his family was one of the original 300 families that comprised Austin’s colony. Bell was the man left in charge of the colony when Austin went to Mexico in 1821.

Josiah H. Bell first settled near Washington on the Brazos, but in 1824 he moved to what is now Brazoria County and pitched camp on a creek that has since been called Bell’s Creek. About a year later he moved to his property fronting the Brazos River and built a “good dwelling house.” Andrew P. McCormick in his book Scotch Irish in Ireland and in America, gave the exact location of this house at the intersection of Austin Street and Front Street, according to the early plat.

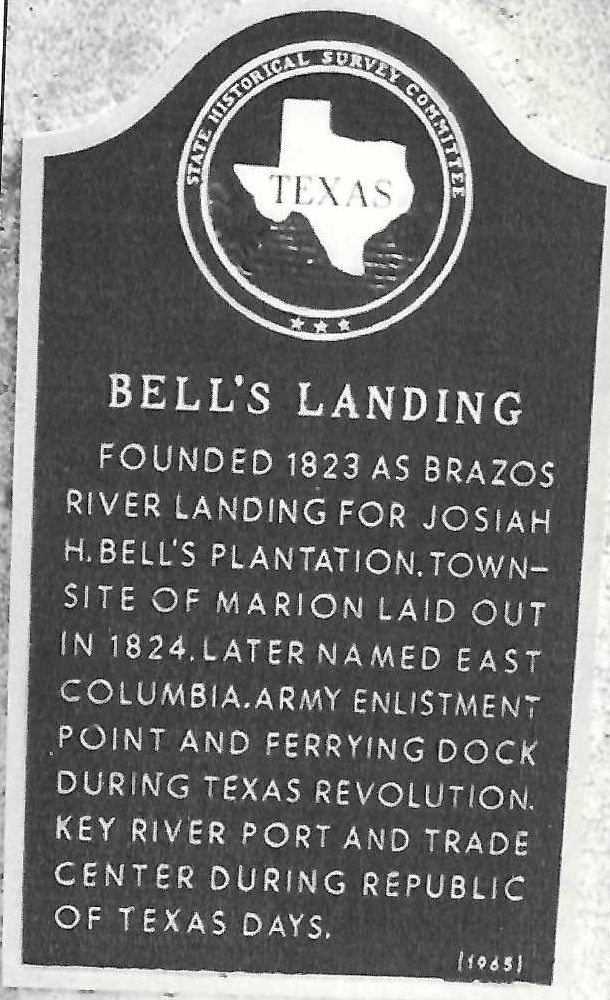

The town of Marion (soon called Bell’s Landing) was planned as a depot for supplies. Bell erected docks, log lined with timbered steps. Soon there were sheds and storerooms, as well as a few houses. Columbia lay two miles down the prairie from Bell’s Landing, at the end of a broad road cut through the timber. The surroundings were beautiful, studded by majestic live oak trees and luxuriant growth of a wide variety of plants. The road from Bell’s Landing was straight but not smooth, and was often covered by a deep trace of slush.

In 1827, Josiah H. Bell moved to his plantation home, south of the town of Columbia, where he lived until his death in 1838. Andrew P. McCormick described this house in great detail. It was a double log house containing six rooms, with a separate kitchen, surrounded by fields, stock lots, orchards, negro quarters, a blacksmith shop and other outhouses. Squire and Mme. Bell offered hospitality and accommodations to a multitude of visitors. Thomas Pilgrim described their home as a “welcome home to every stranger, where the hungry are fed, the naked clad, the sick nursed.” Most itinerant preachers were frequent visitors, as well as the president of the Republic who also used an office in the Bell yard.

Bell’s Landing (Marion) flourished as the port town. It was about 35 miles from the mouth of the Brazos River at Velasco. Although the Brazos River was navigable for an additional 15 miles upstream, Bell’s Landing became the head of most navigation because of its location. It was accessible from the natural highways, the prairies on either side. A schooner trip often was a long drawn out affair, taking several days if the wind was right, and equally as long at anchor if the wind was not right. Mary Austin Holley writes of spending five days—five very seasick days—rocking on board a schooner anchored at the mouth of the Brazos, waiting for a prevailing wind. Another factor that made boat travel difficult was the very treacherous bar at Velasco. Three vessels were lost at this bar in one year, and at one time the wrecks of four different ships were in view. However, in spite of the problems involved, boat travel was the most common means of transportation. Land travel was by horseback or by wagon, and was complicated by the poor roads, which were largely trackless courses laid out by compass.

Most of the first settlers came with Austin’s colony, attracted by the cheap land. Farmers received a labor of land (177 acres); cattlemen a league of land (4,428 acres), and farmers who raised cattle received additional land. A missionary wrote that Texas was peopled with outlaws and renegades. Newcomers were often asked what their name was before they came, or what they were running away from. Actually, Austin made every effort to ascertain that his colonists were men of good character. The rules of the colony provided that “no frontiersman who has no other occupation than that of hunter will be received—no drunkard, no gambler, no profane swearer, no idler” and these rules were enforced.

One of the requirements of the Mexican Government for the early Texas settlers was that they embrace Catholicism. This was never strictly enforced; early settlers began almost at once to practice their own religion. Austin said he found his colonists did not mind contributing to the support of the Catholic Church if they were not compelled to embrace it.

The growth of Bell’s Landing was chronicled by Mary Austin Holley during her many trips to Texas. In 1831 she listed “two or three cabins, a country store and one frame house painted white.” In 1835, she wrote “Marion has increased some two or three dwelling houses and one large warehouse built by Mr. White.” In 1836 she told of “an increase of dwelling houses, and several large warehouses, one of which was built by an extensive dealer in cotton.” William Fairfax Gray wrote in 1837 that Marion consisted of “about eight or ten houses of all description, mostly shanties,” and described Hall’s Tavern as “a perfect shell, dirty and crowded, surrounded by mud.”

There are frequent references in the early diaries to Walter C. White, who came to Texas in 1821, and was later associated with Col. James Knight in many enterprises that made them very rich men. There was a trading post at Fort Bend, a store at San Felipe, a trading schooner, a warehouse at Bell’s Landing, and the general mercantile store at Columbia known as W.C. White & Co. This last store building was used by the government while Columbia was capital.

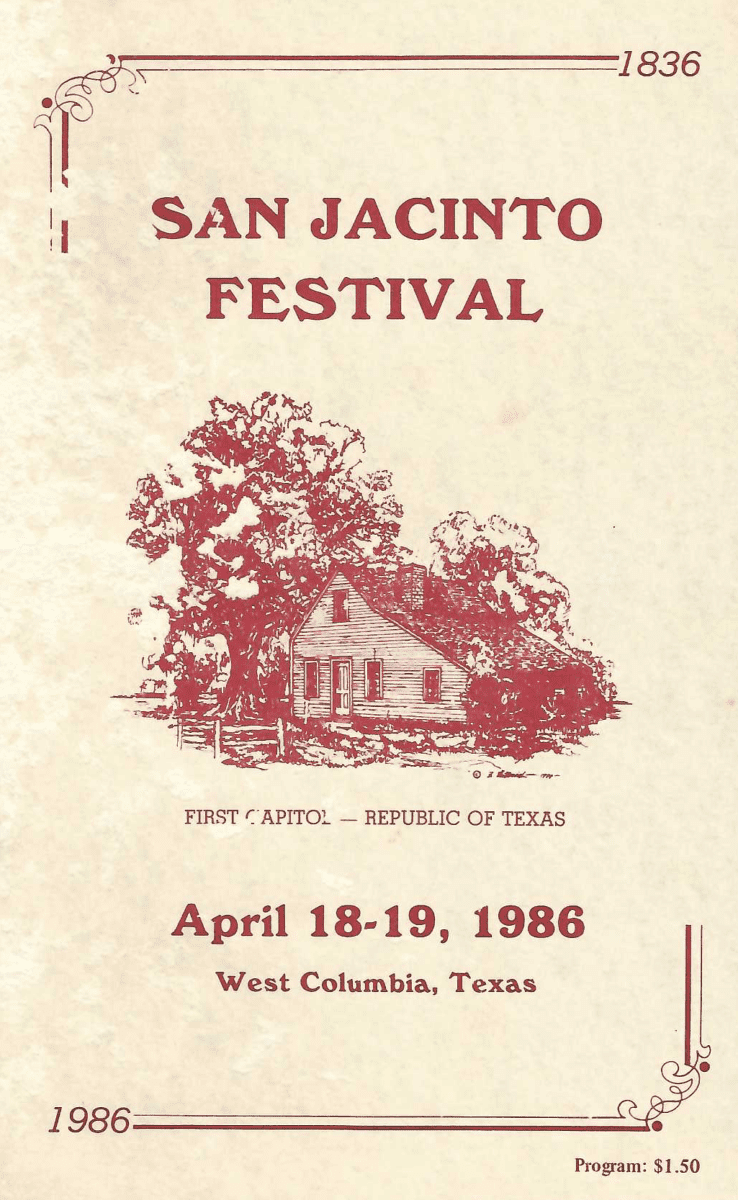

Columbia grew more rapidly than Bell’s Landing. David Edward described Columbia as “the second most important town in the Brazos Department by reason of its location, since it commands trade throughout this area famed for cotton growth.” In 1834 Columbia became the seat of the municipality. It was moved from Brazoria after the severe cholera epidemic in 1833, when so many people died. Brazoria was declared a sickly place, damp, in the middle of a swamp and unhealthy. The seat of the courts was moved to Columbia which being on higher ground was considered healthier and more suitable. Mary Austin Holley described Columbia as “a place of considerable business … contains a hotel kept by Bell, new and spacious—the largest building there. There is besides a building or two, constructed while it was the seat of the courts, for a courthouse, and offices, etc., and a few dwelling houses.”

Living conditions ranged from the meagerest sort of existence to the more luxurious life on the plantations. Most people lived in log cabins or log houses. These varied from a single room cabin with dirt floors and openings covered only with skins or cloth, to the more spacious double cabin. A double log cabin was composed of two rooms parallel to each other separated by a central floored space covered by a common roof—effecting a sort of open ended hall that served both rooms of the double cabin. Noah Smithwick told of visiting a very simple pole cabin, where the entire family was dressed in buckskin. They used stools around a clapboard table, eating on wooden platters with forks made of a joint of cane. He stated that though he never saw this family again, he was told that they prospered and, in a few years built a very comfortable brick house.

Furniture was limited to what could be knocked down and brought in by boat or wagon, or made after the settlers arrived. Most of the furniture made in this area was very simple and utilitarian with clean lines and little decoration. Some used the simple “one leg bed” which was placed in a corner and constructed of rails running from the one leg to the walls, with hemp ropes or rawhide stretching from rail to rail to support the mattress. Mattresses were made of feathers, shucks, or dried grass or moss, depending on what was available. Mary Austin Holley described the way to make a mattress from moss, by burying the moss until it decayed, then placing it in a covering. Most cabins were furnished with bedsteads, homemade tables and stools or chairs with rawhide bottoms. Since there were no closets, all belongings were stored in chests or trunks, or kept on shelves or wallboards. One early settler itemized all the things that were stacked on the shelves over the windows and doors in his cabin.

On the other end of the spectrum, life on the plantation was comfortable and very easy, with necessities and luxuries being shipped in from the states. Many plantation owners came with money and lived very well here as they had before; others prospered after they arrived. The plantation houses were the settings for many parties. Any and every occasion was good for a celebration—visits, weddings, military victories or anniversaries. Often the parties lasted long into the night, with the guests spending the night, filling all the beds and making pallets on the floor. Music was furnished by whatever was available—a fiddle, discordant violin, a hoe scraped by a knife, or on one occasion, singing accompanied by a clevis. The Texans loved to dance. When rough puncheon floors became too painful, boys in moccasins would borrow shoes, so that they could take a turn dancing. Social life was plentiful and varied. There is evidence of a well-supported theater in Columbia in 1836, and horse races in 1834-35, with Josiah H. Bell serving as proprietor of the Columbia Jockey Club. P.R. Splane of Columbia wagered $10,000 on his horse in a local newspaper.

Plantations flourished for many years, raising large crops of cotton and sugar cane. Many cattle were also raised, so that meat was very cheap. At one time the banks of the Brazos River were covered with carcasses of cattle slaughtered for their hides and left to decay. There were many plantations in the immediate vicinity of Columbia, some of them being Bell’s, Waldeck, Osceola, Orozimbo, Underwood, Tinsley and Patton. The plantation house built by Columbus R. Patton on land originally owned by Martin Varner is now known as the Varner-Hogg Museum and is the only plantation house still standing in this area.

Schooling was often rather sketchy. Many of the more affluent sent their children back to the states for education. The first English school was held in 1829. Josiah H. Bell built a school house about one mile west of the town of Columbia. Mr. Thomas J. Pilgrim taught there and in Columbia intermittently from 1831-36. Schools were also held at various plantations and in the old capitol building, often with the local minister serving as teacher. Though school books were scarce, blue backed spellers, red backed readers and elementary arithmetics were used. There was a Columbia Institute in 1844, and the Columbia Female Seminary for Young Ladies was held at the old Marion Hotel in Columbia in 1845.

The first Bible Society was established in Columbia in 1835. Religious services were often a community affair; many were held in the building used by the Senate. President Sam Houston ruled in October 1836 “that the Senate Chambers be cleared for the purpose of having public preaching there every Sabbath day.” A Presbyterian minister and an Episcopalian minister alternated as chaplain to the senate of the first congress of the Republic. There were early Methodist circuit riders, but no Methodist Church was organized until 1840. The Presbyterian Church was also organized in 1840, being the third Presbyterian church organized in Texas.