![]()

By Tracy Gupton

Columbia Historical Museum Board Member

A little more than 30 years separated jury verdicts in Brazoria County murder trials involving the killing of two men in the Columbia area. The common threads sewing the unrelated murders together – in addition to them happening in West Columbia and East Columbia – were the similar juries’ verdicts and the fact that the father of the defendant in the latter trial had served as foreman of a jury in a civil suit that spurred the earlier killing 32 years prior to the one involving his son.

The quiet little community of Columbia was thrust into newspaper headlines in early June 1874 and again in April 1906. On both occasions, the killing of local men was the cause; and both shootings were the result of long simmering feuds on the level of the famed Hatfield and McCoy family wars.

Edward Haney Sweeny served as the foreman of the jury hearing the civil suit in Brazoria County on May 9, 1874, brought against Joseph Manson Tinsley by William C. Boykin, who claimed Tinsley owed him a little more than $600, a debt Boykin said Tinsley refused to pay. Ed Sweeny, a descendant of the man the nearby town of Sweeny on Chance’s Prairie was named for, John Sweeny, and the other members of the jury decided in Boykin’s favor. Joseph Tinsley quickly announced plans to appeal their verdict, which allegedly resulted in Boykin threatening to kill Tinsley if the court reversed the jury’s decision.

A story in the April 4, 2005, edition of The Brazosport Facts recounted that just before noon on June 1, 1874, Joseph Tinsley and his brother, Charles Tinsley, approached Boykin in front of Wilson’s Saloon on West Columbia’s main street. Joe Tinsley demanded that Boykin “retract certain declarations he had made in regard to Tinsley’s wife and (Joe) Tinsley himself,” The Facts story revealed.

“I came to kill you, Boykin,” uttered Joe Tinsley while Boykin was sitting on the steps of the saloon, leaning against a post. The Facts’ story said that Boykin got up and stepped inside the saloon’s front door, then returned to face the Tinsley brothers, saying, “I take back nothing.”

Those were likely William Boykin’s final words. The blast from Joe Tinsley’s shotgun struck Boykin in the chest and stomach, reportedly killing him instantly. What originated as a war of words between two West Columbia area men who simply did not like each other, with ample reason, had boiled over into a showdown at Wilson’s Saloon at almost high noon.

Local Justice of the Peace N.H. Jones arrested the Tinsley brothers and charged them both with murder, Charles Tinsley, because he was aware of his brother’s intention to kill Boykin that day and did nothing to prevent it. The brothers were the sons of well- known, early pioneers of the Columbia area, Isaac and Mary Tinsley, who owned a thriving cotton and sugar plantation near Varner Creek prior to the Civil War.

The county courthouse was located in Brazoria in the 1870s. The Tinsley brothers were indicted for murder by the county grand jury in October 1874, but the jury that heard the case in May 1875 failed to reach a verdict. District Judge A.P. McCormick declared a mistrial, and the Tinsley brothers were released on bond. Their defense attorney, A.S. Lathrop, asked for yet another continuance in October 1876 because several of his defense witnesses had not been served or were unable to attend the second murder trial on that date.

Lathrop specifically mentioned the need for testimony from the Tinsley brothers’ sister, Annie Westall, who supposedly was too ill to leave her Houston home to make the trip to Brazoria. Lathrop wanted his clients’ sister to tell the jury how Boykin had gone to her home and threatened to kill her brother Joseph.

The Facts’ 2005 retelling of the Boykin murder case said that Annie Westall asked Boykin if he “was not afraid he would be hung” for killing her brother, to which Boykin allegedly replied, “Dead men tell no tales.”

John Snow was to testify at trial that Boykin displayed a pair of Derringers to him, telling the jury that Boykin told him he intended to use them to kill Joseph Tinsley “the first good chance he got.”

Judge William Burkhart eventually presided over the follow-up murder trial in Brazoria where W.N. Payne of Columbia gave a deposition saying he talked to Boykin after the jury in the civil trial sided with him. Payne testified that Boykin said if Joseph Tinsley won his lawsuit on appeal, “either he (Boykin) or Tinsley had to die.”

William Boykin had been in his grave for some 34 months before a Brazoria County jury, led by George Beall as foreman, acquitted the Tinsley brothers of murder. Their father, Isaac Tinsley, came to Texas from Alabama in 1830 and fought in the Texas Revolution. Isaac Tinsley died a couple months prior to the killing of Boykin.

Another man shot down in the street in East Columbia on April 12, 1906, was a Civil War veteran who served in Brown’s Regiment of the Confederate Army. His killing also resulted in heavy media coverage.

The Houston Post ran an early story on the East Columbia shooting, praising Wilson Davis as “highly respected” and writing that “the deplorable affair has cast a gloom over this entire vicinity.”

What was left out of that Houston Post story was the fact that Wilson Davis served time in the state penitentiary for killing his son-in-law, 22-year-old Thomas Sweeny, in 1895 when Thomas’s baby boy was only 8-months old.

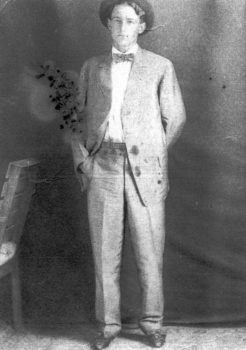

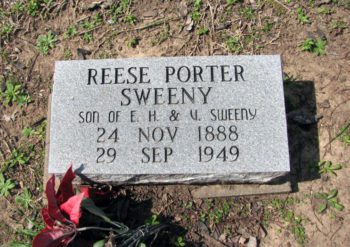

Both Wilson Davis and Reese Porter Sweeny, the young man who killed Davis, are buried at historic Columbia Cemetery in West Columbia. Reese Sweeny, who was only 17 when the highly publicized killing occurred, was the younger brother of Thomas Sweeny.

Both Sweeny brothers were the sons of Edward Haney Sweeny, who served as foreman of the jury in the 1874 civil trial involving William Boykin and Joseph Tinsley that lit the fuse for the explosive shotgun blast on West Columbia’s main street a few weeks later that claimed the life of Boykin.

A September 13, 1895, newspaper story reported that Wilson Davis was arrested by a Wharton County sheriff’s deputy without incident several days after he killed Thomas Sweeny. The newspaper story read, “The prisoner was well armed and could have made a desperate fight but listened to the wise talk of the posse and surrendered.”

Davis also was armed with a shotgun when he rode his horse in front of W.L. Crews’ store in East Columbia the afternoon of April 12, 1906. After serving a 5-year prison sentence for the killing of his son-in-law, Wilson Davis allegedly pledged to kill every member of Thomas Sweeny’s family upon his release from the state pen.

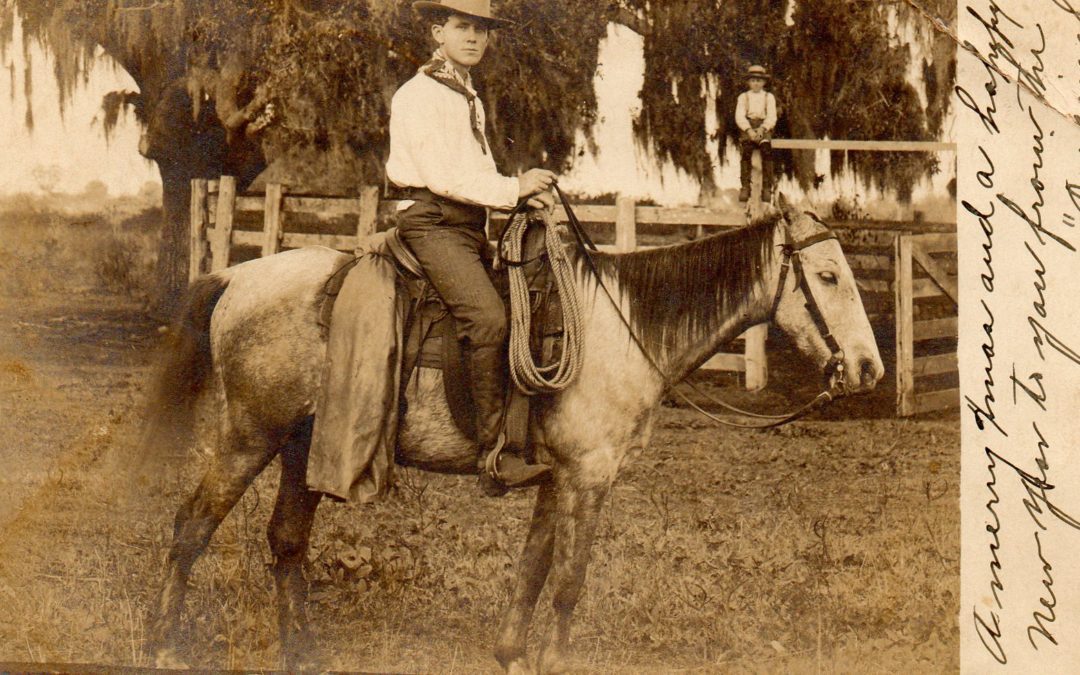

Reese Sweeny had been visiting with Samuel “Buff” Gupton, a clerk at W.L. Crews’ store, inside the building on the corner of Main Street and West Columbia Avenue in East Columbia when Wilson Davis approached on horseback, apparently unaware that one of Thomas Sweeny’s brothers was nearby. The teenager reportedly stepped onto the outside gallery of the store, brandishing a shotgun, and locked eyes with his brother’s killer.

The younger man was quicker and fired his shotgun, knocking Davis out of his saddle when the buckshot struck the 61-year-old man in the face and neck. Davis’s brother, Cornelious Davis, was in town at the time at the nearby Masonic Lodge and was quickly on the scene of his brother’s killing.

Gupton, whose father Sam Gupton ran a meat market and store a block away, rushed outside W.L. Crews’ store when he heard the shotgun blast and witnessed Wilson Davis laying dead in the street.

Gupton’s testimony at Reese Sweeny’s murder trial at the courthouse in Angleton helped persuade the jury that the teenager had not gone gunning for Wilson Davis that day but rather reacted in self-defense. Gupton, who would later serve more than 20 years as West Columbia’s postmaster, was only 20 years old at the time of the killing. He testified that Reese Sweeny had been calm and spoke with him in a friendly manner inside the store.

But the defendant went on the defensive once stepping outside the Crews store. “When Davis seemed to recognize Reese and reached for and grasped his shotgun, Reese believed Davis planned to carry into execution his threats to kill him,” Marie Beth Jones writes about the 2006 incident in her book, “Trials and Tribulations: Early Texas Crime Stories.” At that point, Jones wrote in her book, “Reese raised his gun and fired quickly, at which time Davis, still grasping his shotgun, fell from his horse.”

Jones, a former managing editor of The Angleton Times and current columnist for The Facts, wrote that Reese Sweeny was finally tried for Wilson Davis’s killing on February 18, 1908.

“Either Reese’s claims of self-defense, Gupton’s testimony about the defendant’s calm state of mind just before the shooting, or Davis’s threats and general reputation for violence must have carried the day, as the trial jury, led by F.M. Phipps as foreman, found Reese Sweeny not guilty,” Jones wrote in her book, published in 2009.

Reese Porter Sweeny was named for his relative, former Brazoria County Sheriff Rees Porter Sweeny who is also buried at Old Columbia Cemetery. The former sheriff, a native of Tennessee, was a nephew of John Sweeny who the town of Sweeny is named for. This Rees Sweeny later served as a deputy U.S. marshal after his term as county sheriff ended. He spelled his first name without the ‘e’ on the end like the younger Reese Sweeny.

These twin killings from more than 100 years ago were fueled by long simmering family feuds and reflect an era when the wild, wild west behaviors were still prevalent, and juries still took into account threats of violence made against the defendants by their victims when levying their judgments in Brazoria County courthouses in Brazoria and Angleton.

Samuel “Buff” Gupton was 20-years old, clerking at the W.L. Crews store in East Columbia, the day Wilson Davis was gunned down in the street in front of the store in 1906. Buff Gupton was a retired West Columbia postmaster who ran small grocery stores in East Columbia and West Columbia prior to being named West Columbia’s postmaster.