![]()

By Benjamin Tumlinson

Columbia Historical Museum

I had the privilege of living in six states and two other countries, not counting the United States. As I traveled in these other states and foreign lands, I would often gaze out at the various landscapes and daydream about how our ancestors might have traversed the sometimes-difficult terrain. I imagined the trials and tribulations they may have experienced. It would harken me back to my elementary school days when I had the opportunity to play “Oregon Trail” on the school’s desktop computer. Inevitably, the game would take me to a river crossing, and I would be presented with a choice of trying to ford the river; or, if I had enough money, I could pay to cross the river on a ferry.

The selection of the location for Columbia was not an accident. Stephen F. Austin, the Father of Texas, selected the area for colonization in 1821 because of its access to the Gulf and its rich, river-fed bottom lands. He recognized the potential of the Brazos River as an incoming source of transportation for immigrants and supplies to the new colony and as a means by which its crops could be ferried to market. (National Register of Historic Places, Transportation and Settlement Along the Brazos River, 1991)

Although the Brazos and San Bernard rivers served as the thoroughfare for people and commerce, they also represented a natural barricade. In the early days of Austin’s colony and of the Republic, there were no bridges. To get goods to market, or simply to travel, these rivers had to be crossed. Before modern bridges were constructed to span Texas rivers, ferries were maintained at most points where roads crossed streams or rivers that were not fordable. (Anonymous, “Ferries,” Handbook of Texas Online). These ferries represented a lifeline for the people and the growth of the newly forming Texas settlement and later the Republic.

Ferry regulations important to colonies’ health

These river crossings were of vital importance and had to be maintained. Austin understood the importance of these ferries and established regulations to govern them. From the beginning, ferries were subject to regulation by the communities they served, and, as early as July 1824, Austin and Baron de Bastrop issued a license to John McFarlan, giving him the exclusive privilege of operating a ferry at San Felipe de Austin, but stipulating certain duties he must fulfill to retain the charter. (“Ferries,” Handbook of Texas).

Later, when the Republic of Texas formed a government, this regulation became a matter of great importance. In fact, it was one of the first items of business for the newly formed government.

On December 20, 1836, one of the first acts of the Congress of the Republic of Texas regulated ferries, delineated their responsibilities to the public, and required that they be chartered by the county in which they operated. (“Ferries,” Handbook of Texas).

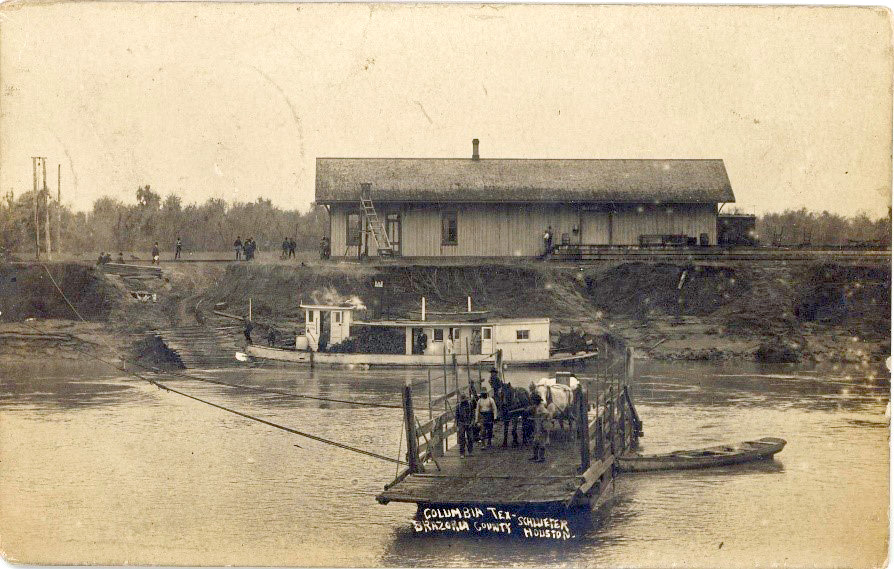

If the Brazos River and the river port of Bell’s Landing represented the heart of the early economy, then the ferries were the connecting veins and arteries. The most prevalent type of ferry was constructed to take a cart or wagon across. Most ferries also had a cable or rope system fastened to each riverbank to act as guide across.

Black’s Ferry founder buried in Old Columbia Cemetery

I want to highlight a ferry that connected us with our neighbors to the east – yeah, those folks who hail from Sweeny and the surrounding area. Black’s Ferry served as a vital connection between the two communities traversing the San Bernard River that separated them. You may or may not be familiar with it, but Black’s Ferry was one of two ferries that connected goods and people from Old Ocean and the Sweeny area to Columbia, all a part of the original land grants given by Austin. This area is probably known better as Chance’s Prairie when Black’s Ferry was first operating. You probably traveled the bridge over the San Bernard on FM 522 and never realized this was once the site of a crucial ferry connection between our two communities.

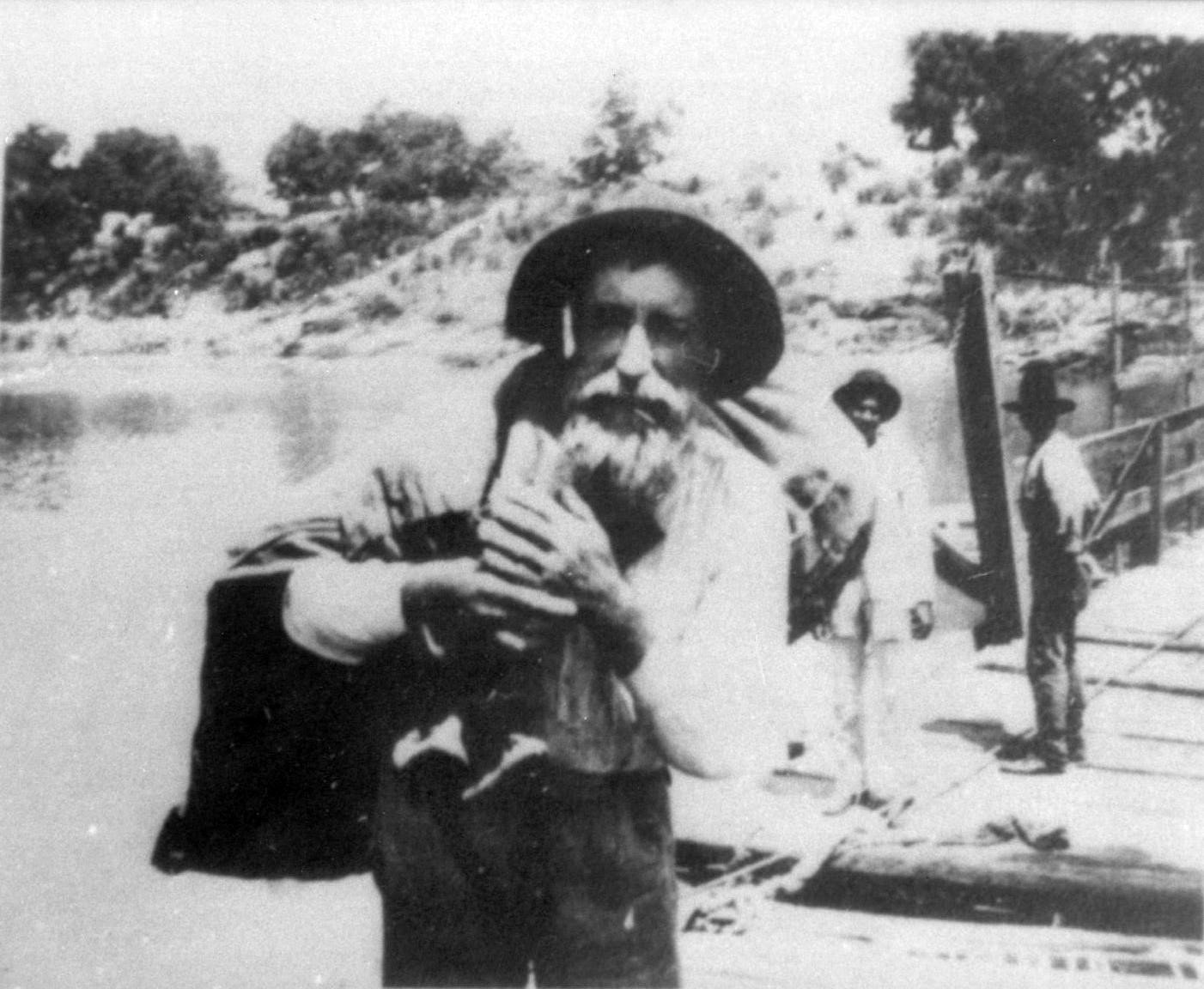

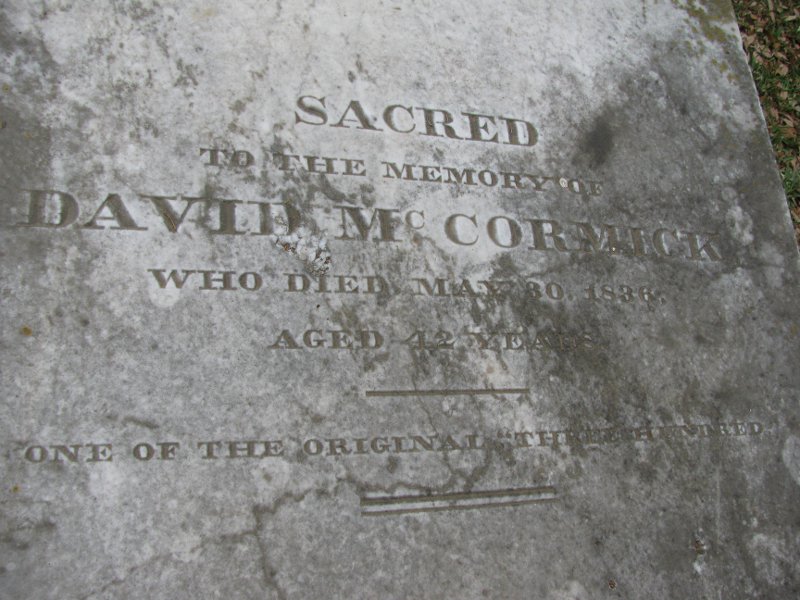

This ferry has an interesting history and has changed ownership several times starting in 1824. The land that bordered the west side of the San Bernard River first belonged to David McCormick. McCormick was among those who contributed 630 bushels of corn in 1823 to pay the expenses of Erasmo Seguín, who was serving as Texas representative to the Mexican congress. McCormick died on May 10, 1836. He was buried near his home, but the body was later moved to West Columbia. (Kleiner and Johnson, “McCormick, David,” Handbook of Texas Online) His grave is counted amongst the oldest in the “Old Columbia Cemetery”. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/9416819/david-mccormick The land and the ferry operation remained in the family until 1845.

David McCormick’s grave in Old Columbia Cemetery. Photo courtesy Findagrave.com

James E. Black purchased 1,000 acres from the McCormick estate 1845. It is said he paid $10,000 in gold coins, got the land, two boats and a household. From this point, Black continued the ferry, developed his plantation, and built a sugar house, thus the beginning of the name and history of “Blacks Ferry”. (Black’s Ferry History, Internet) The ferry and the land were passed to his wife Sarah in 1858 on James’ death. She and her sons operated the ferry until 1870.

The ferry and land were sold to Vincent Tureni. Upon his death, William L. Sweeny, administrator for the Tureni Estate sold the property at a public auction to his brother J.W. Sweeny, who then sold it back to William on the same day. The land is described as 200 acres with improvements including a ferry and ferry privileges and the homestead of Tureni. (Black’s Ferry History, Internet)

William L. Sweeny is noted to have reopened a post office in the area. Shortly after this, the town of Sweeny was developed. On July 23, 1909, William L. Sweeny was appointed postmaster of “Sweeny, Texas” and, in 1911, Burton D. Hurd laid out the town. (Creighton) William L. Sweeny died in 1923.

History is unclear exactly how long the ferry remained operational. County records go silent as far as crossing the Bernard at “Blacks Ferry” up until 1946 when the county entered into an agreement with J. S. Abercrombie Company to construct a pontoon bridge across the Bernard at “Blacks Ferry”. (Black’s Ferry History, Internet) http://sweenytexashistory.com/images/BlacksFerry/BlacksFerry.pdf

The use of ferries faded into history with the construction of bridges, draw bridges, and the introduction of rail to the area. In 1860, the Houston Tap and Brazoria Railway, with tracks from Fort Bend County to East Columbia, was the first railroad in Brazoria County. By 1905, the St. Louis, Brownsville and Mexico railroad had reached Sweeny, which was briefly known as Adamston during that time. This line connected Adamston to Brazoria and Angleton. By 1907, the International and Great Northern Railroad connected East Columbia to Houston and the Velasco, Brazos and Northern Railway connected Angleton to Velasco.

Ferries of the area are inextricably linked to the history of West Columbia and were, in their own way, tied to the health of the fledgling Texas settlement.