![]()

FEBRUARY IS BLACK HISTORY MONTH

By Tracy Gupton

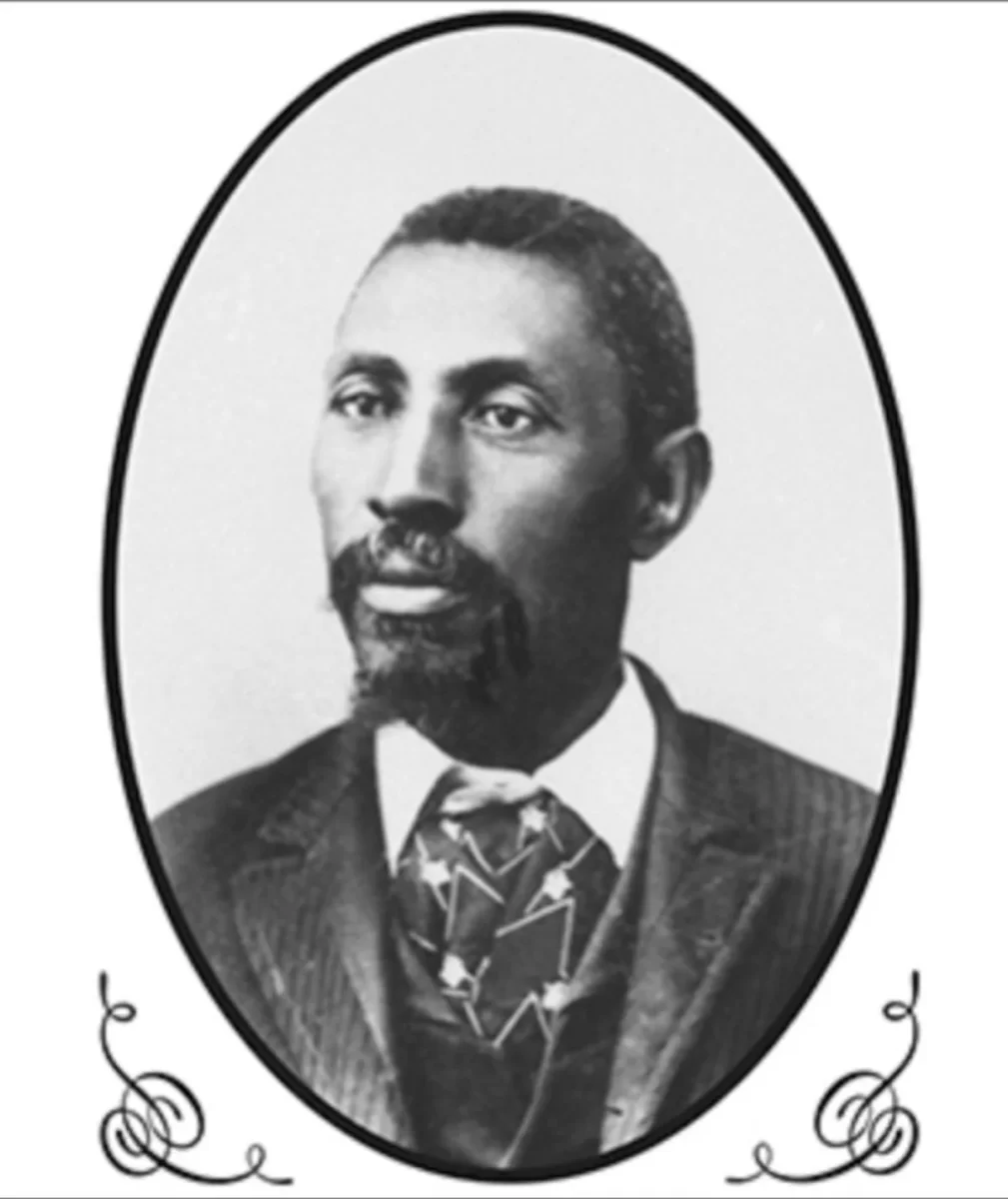

Nathan H. Haller was living in Brazoria not too far from West Columbia when he won a seat in the Texas House of Representatives to represent Brazoria and Matagorda counties, thus becoming one of the few Black Texans to serve in the state legislature after the Civil War. The former slave is honored at the Columbia Historical Museum with a display year round, not just during Black History Month, that features a large photo and newspaper story on the former state representative.

A resolution introduced in the House of Representatives in 2003 by former State Representative Dennis Bonnen of Angleton said that, “Whereas, born a slave on July 8, 1840, Mr. Haller moved with his master to Walker County, Texas, at an early age, serving his master until he was given his freedom on June 19, 1865; upon receiving his freedom, Mr. Haller remained in Walker County as a farmer and was elected county commissioner for a number of years.”

A story in The Bay City Sentinel newspaper revealed that the former slave represented Brazoria and Matagorda counties in the Twenty-third and Twenty-fourth legislatures after first becoming active in Republican party politics in the Huntsville, Texas, area. “By 1892 he had moved to Brazoria County,” the Bay City newspaper’s story said. “He was living in Brazoria when he won a seat in the Texas House of Representatives to represent Brazoria and Matagorda counties. Two years later he was defeated in a close election by R.C. Duff. However, the House Committee on Privileges and Elections ruled that the Brazoria County judge had failed to count certain votes from Matagorda County that gave Haller a 50-vote margin of victory.”

According to the newspaper’s story taken from the Handbook of Texas Online, Haller became one of the last two Blacks to serve in the Texas House of Representatives between the nineteenth century and 1966. He represented the citizens of the West Columbia area in Austin between 1893 and 1897.

“In the House he sat on the Roads, Bridges and Ferries, Labor, and Penitentiaries committees,” the Bay City Sentinel story continues. “He unsuccessfully introduced a bill that would have established a branch of the University of Texas for Blacks and opposed efforts to divide Brazoria County and dilute the Black vote.”

Dennis Bonnen’s House Resolution Number 295 stated, “Whereas, former State Representative Nathan H. Haller was a notable Texan whose passing on February 27, 1917, at the age of 76, left a gap in Texas history to be bridged over a century later by the echoes of his achievements and accomplishments; and whereas, in the late 1880s or early 1890s, Mr. Haller moved to Brazoria County and was elected state representative to the 23rd Legislature, and he also served in the 24th Legislature; and whereas, Mr. Haller was the only African-American Texas state representative in 1893 during the 23rd Legislature; he served on the Roads, Bridges and Ferries Committee as well as the Labor Committee.”

The Bay City Sentinel story said that Haller was born in slavery in Charleston, South Carolina, and he continued working the fields of Walker County as a free man at the conclusion of the Civil War. He married Paralee Jordan of Huntsville and the farmer and his wife had two children. Following the death of Paralee, Nathan married Annie Butcher of Walker County, and he fathered three more children with his second wife.

He moved from Brazoria to Houston when his second term in the state house of representatives expired and Nathan Haller was working as a wagon driver in 1910.

Information on Nathan Haller gleaned from Wikipedia reveals that he also worked as a blacksmith in addition to farming the land he owned in Brazoria County and later Harris County. According to Wikipedia, Haller and Robert Lloyd Smith were the last two African Americans to hold state office in Texas between the end of the Civil War until Barbara Jordan of Houston was elected in 1966 when the Civil Rights movement in America brought more opportunity for Blacks to successfully run for public office.

A story found online written by Ronald Howard Livingston revealed that Haller purchased about 11 acres of land in Brazoria in 1888 from Charles Tunstall and, over the next decade, Haller “was involved in the buying and selling of several lots in the towns of Angleton and Velasco.

“Following his governmental service, Nathan continued residing in Brazoria County where in 1900 he was working as a day laborer,” Livingston’s story goes on to say. “By 1902, he was a resident of Houston.”

Nathan H. Haller died at his home on Dowling Street in Houston on February 27, 1917. He was survived by his second wife Ann and his five children: Stonewall Jackson Haller and James Haller, the two sons he and his first wife Paralee had, and Joseph J. Haller, Monroe D. Haller and Jemima Haller, his three children with his second wife, Matilda Ann Butcher.

“Mr. Haller served as a voice for his district, an instrument to education, and a shoulder to his people,” Dennis Bonnen’s House resolution states. “He is to be commended and applauded for his courageousness, endurance, loyalty, and most notably, his bravery in overcoming conditions many would not have challenged 30 years into their freedom.”

The Columbia Historical Museum, located at 247 East Brazos Avenue in downtown West Columbia, includes exhibits year-round on former local Black business leaders like the Viola and Snow families, cowboys like Austin Williams and political figures such as Nathan H. Haller. The museum is open every Thursday, Friday and Saturday from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. and tours can be arranged to visit the historic Rosenwald School located directly behind the museum at the intersection of Clay and Broad streets. The Rosenwald School once served as the one-room schoolhouse for Black children during the days of racial segregation.

February is Black History Month. There will be an open house at the Rosenwald School on Saturday, February 8th.

Contact the museum at (979) 345-6125 for more information.