![]()

By Tracy Gupton

Halloween 2023. What better day than today to focus on one of the dozen or so stories told by former reference librarian at the Brazoria County Library Catherine Munson Foster in her popular 1977 book, “Ghosts Along the Brazos.” Angeline Caldwell Kerr, the subject of Foster’s “Ghosts Along the Brazos” chapter, “A Strange Happening,” will be one of five women of notoriety in Brazoria County history being portrayed at Saturday’s “Meet Your Ancestors” program.

West Columbia poet Edie Weems will be dramatizing the young life of “Angie” Kerr at Angeline’s grave site at historic Columbia Cemetery between 5 and 7 p.m. Saturday, November 4th, when the Columbia Historical Museum in cooperation with the Columbia Cemetery Association host their annual joint event. This year’s “Meet Your Ancestors” will feature Tina Crawford portraying Rachel Carson Underwood, Sarah Lamb portraying Mary McKenzie Bell, Mary Wooderson Holler acting as Zula Winstead Loggins, Kaye Crocker presenting Beth Ferguson Griggs’ life story, and Edie Weems portraying Angie Kerr.

Saturday evening’s event is free and everyone is invited to participate. The event will kick off at 5 p.m. Saturday at the main gates of Columbia Cemetery on East Jackson Street across the street from Columbia Methodist Church. There will be guides on hand to lead small groups from one burial plot to the next of the five women being highlighted at this year’s “Meet Your Ancestors.”

The late Catherine Munson Foster was a descendant of one of the 300 or so families who joined Stephen F. Austin in the early 1820s in comprising Austin’s original Anglo pioneers in the Eastern section of Mexico that would become Texas. Rachel Jane Carson, Mary McKenzie Bell and Angeline Caldwell Kerr also were involved in the migration from Western Louisiana into Mexico with Stephen F. Austin in 1821.

A large, flat concrete burial crypt lies at Old Columbia Cemetery marking the location where Angie Kerr’s remains were reportedly buried in the 1850s, several decades after her life ended in 1825 in the neighboring town of Brazoria. Two of her three children died the same year as their young mother, “victims of the fever,” according to Foster’s book that was published by Texas Press of Waco in 1977.

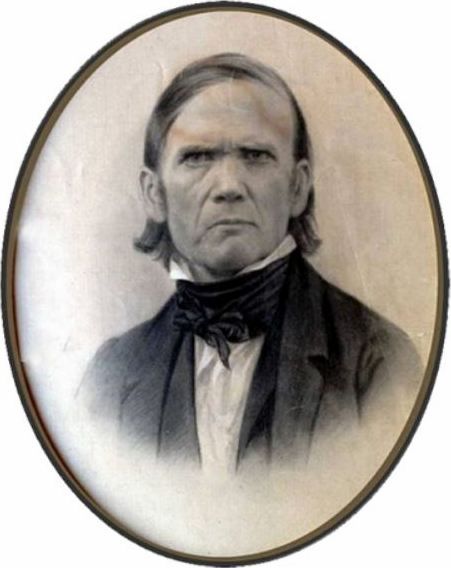

Flat tombstone pictured marks burial site of Angeline Caldwell Kerr at historic Columbia Cemetery in West Columbia

“There is not much to tell about so brief a life,” Foster wrote in her popular book of ghost stories. “She had come with her husband, James, and three small children from a comfortable home in Missouri to the crude frontier settlement of Brazoria. There, after a short time, she and two of her babies died.”

James R. Kerr, a Kentucky native born in 1790, was the son of a Baptist minister. His biography reveals he fought in the War of 1812 and later was a sheriff of St. Charles County, Missouri. James Kerr married Angeline “Angie” Caldwell in 1818 and served in the Missouri Senate and House of Representatives. He was appointed Surveyor General of the Texas colony of Green DeWitt in 1825.

The Kerrs ended up in Brazoria over a decade before Texans won their independence from Mexico in 1836. “The fever” claimed the lives of Angeline on June 27, 1825, when she was only 23 years old.

“When Angeline died her body was sealed in a hollowed-out log for burial,” Foster wrote. “This was far back in the pioneer days when it was often impossible to secure lumber, even for such necessary things as coffins.”

James Kerr, still in the early stages of grieving the tragic death of his young wife, soon had to suffer great loss twice more when he had to bury both of his young sons, 11-month-old baby John James Kerr dying August 9th and five-year-old Isom Caldwell Kerr becoming another “fever” victim on August 30, 1825.

Now the alleged incident that qualified Angie Kerr’s ordeal for a chapter in Catherine Munson Foster’s “Ghosts Along the Brazos” book unfolds as follows: “How long she lay in her singular casket is not known, but it must have been for some years. It is probable that she was first buried elsewhere as Columbia was not founded until 1826. Eventually, however, a more conventional coffin was secured (probably a pine box) and it was decided to transfer the body to a permanent resting place. Then came the strange happening.”

Foster, who used to thrill area children and adults alike with retellings of her many “ghost stories” at local schools and in front of civic groups, wrote in her book, “When the log was split open, the girl was discovered, to the shocked disbelief of the onlookers, lying there as if asleep, as beautiful as she had been in life, and in a perfect state of preservation. Then, as the air reached it, the body turned to dust before their eyes.”

Did this occurrence actually happen? Who knows? The transfer of Angeline Kerr’s remains from the sealed live oak log to a pine box for reburial at Columbia Cemetery happened over 170 years ago.

The visitors to Columbia Cemetery Saturday evening who gather near Angeline’s grave will have a difficult time reading the script on her tombstone which, as Catherine Munson Foster described it, “is a flat one about the size of an ordinary door … the sad little poem carved on its surface can still be read, a poem that puts a fitting period to her sad, brief life.”

Foster wrote that Kerr’s tombstone epitaph reads: “By foreign hands thy dying eyes are closed, By foreign hands thy decent limbs composed, By foreign hands thy humble grave adorned, By strangers buried and by strangers mourned.”

Angeline was born February 8, 1802, in Kentucky, the daughter of General James Caldwell and Meeke Perrin Caldwell. Her mother was a native of Virginia. Both of Angeline’s parents are buried in Missouri, which is where James and Angie Kerr’s children were born.

James Kerr was involved in area politics and law enforcement during the formative years of the Republic of Texas. He was the Lavaca delegate at the Convention at San Felipe de Austin in 1832, after having moved from the Columbia-Brazoria area to Jackson County in 1827. He served in the Republic of Texas army in 1836 and was elected to the Third Texas Congress in 1838.

Sarah Grace Fulton became James Kerr’s second wife and he spent his later years practicing medicine in Jackson County where he died in 1850, a quarter century after the loss of his first wife. Their daughter, Mary Margaret Kerr Mitchell Sheldon, died in 1884 and is buried in a Cuero cemetery in DeWitt County, Texas. Mary Margaret named her daughter Angelina Genevieve after the beloved mother she lost when she was only three years old, living in Brazoria.

Kerr County and the city of Kerrville are named for Angeline’s husband, Texas frontiersman and patriot Major James Kerr. A Texas State Historical Association marker stands on the courthouse square in Kerrville memorializing the former Brazorian who had served as a congressman of the Republic of Texas.