![]()

By Tracy Gupton

Columbia Historical Museum

Juneteenth is celebrated annually across the great state of Texas and beyond, but many are unaware of the event’s origins. With February being “Black History Month” in America, now is a good time to look closer at what “Juneteenth” really means.

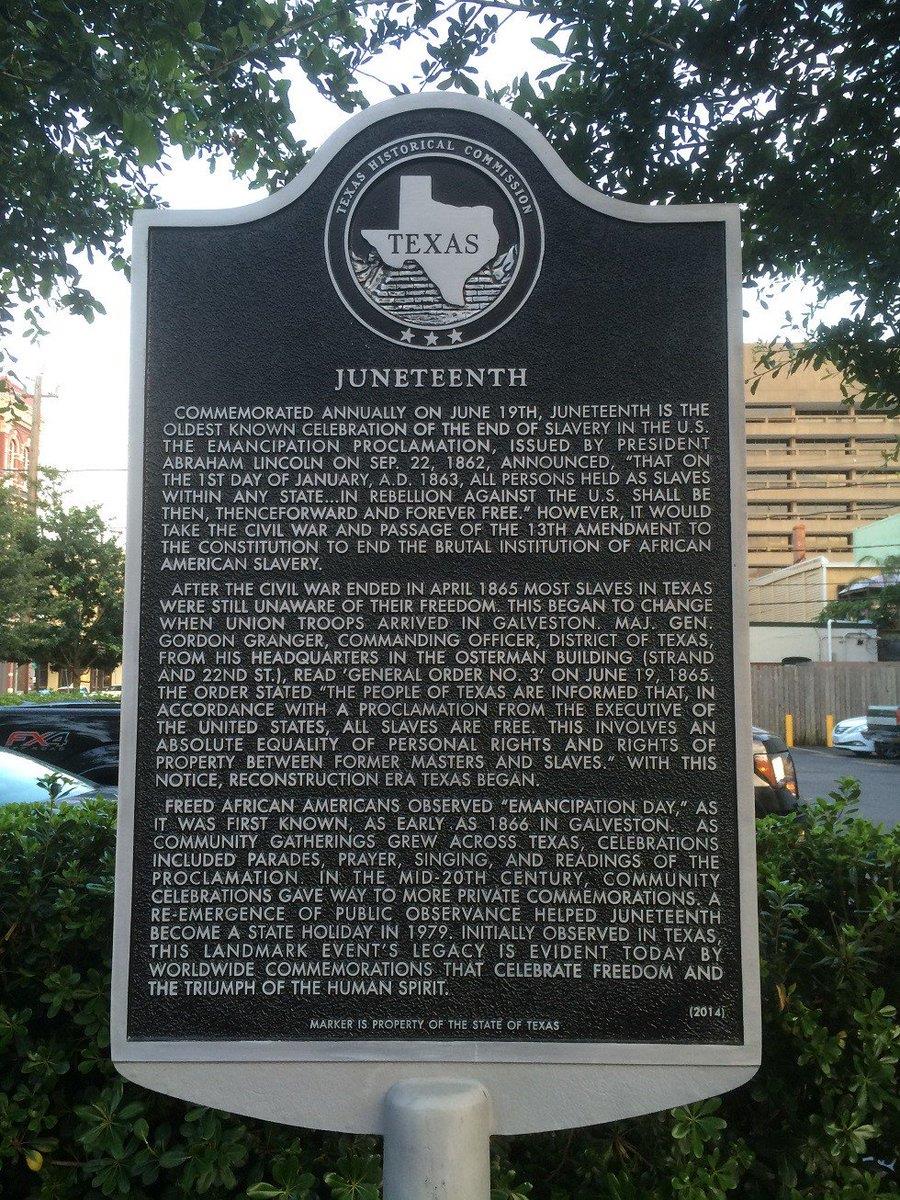

A Texas State Historical Marker dedicated in Galveston in 2014 reads: “Freed African Americans observed ‘Emancipation Day,’ as it was first known, as early as 1866 in Galveston. As community gatherings grew across Texas, celebrations included parades, prayer, singing, and readings of the proclamation. In the mid-20th Century, community celebrations gave way to more private commemorations. A re-emergence of public observance helped Juneteenth become a state holiday in 1979. Initially observed in Texas, this landmark event’s legacy is evident today by worldwide commemorations that celebrate freedom and the triumph of the human spirit.”

Locally the annual celebration of Juneteenth was promoted in West Columbia by wealthy landowner Charlie Brown in the late 1800s and early 1900s. He had been born a slave but came to Brazoria County as a freed man where he later in life was known as the richest Black man in Texas.

February is Black History Month in America

West Columbian Cora Faye Williams was quoted in a 2007 Image magazine article as saying, “Charlie Brown gathered all the people together to organize this big celebration. People came from Houston and other surrounding counties by train or horse-drawn buggies. He brought musicians in from Houston to perform.”

Saying she was too young to attend these Juneteenth celebrations in West Columbia during her childhood, Cora Faye Williams remembered, “Festivities would start on a Friday and go through the weekend. No one else was having celebrations on this date. They would have a brass band come by train to East Columbia, and (Charlie Brown) would send a wagon out to pick them up.”

The annual Juneteenth celebrations are in honor of the arrival of Union soldiers in Galveston after the Civil War ended to inform all former slaves that they were no longer another man’s property.

“Eighteen hundred bluecoats landed at Galveston on June 19, under command of General Gordon Granger, a New Yorker, West Point class of 1845, a competent but little-known officer whose one moment of distinction in the war had come during the Union defeat at Chickamauga 20 months before,” wrote James L. Haley in his 2006 book Passionate Nation: The Epic History of Texas. “There, Granger’s valiant reinforcement of George Thomas without waiting on orders to do so helped prevent a defeat from degenerating into disaster. Upon arrival in Galveston, Granger published several General Orders, outlawing all acts of the Texas legislature since secession, paroling most Confederate soldiers, decreeing that the cotton crop could be sold but only to Northern factors, and most importantly: ‘The people are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free.’”

The Texas State Historical Marker in Galveston reads: “Commemorated annually on June 19th, Juneteenth is the oldest known celebration of the end of slavery in the U.S. The Emancipation Proclamation, issued by President Abraham Lincoln on September 22, 1862, announced ‘that on the first day of January, A.D. 1863, all persons held as slaves within any state … in rebellion against the U.S. shall be then, thenceforward and forever free.’”

However, it would take the Civil War and passage of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution to end the brutal institution of African American slavery. After the Civil War ended in April 1865 most slaves in Texas were still unaware of their freedom.

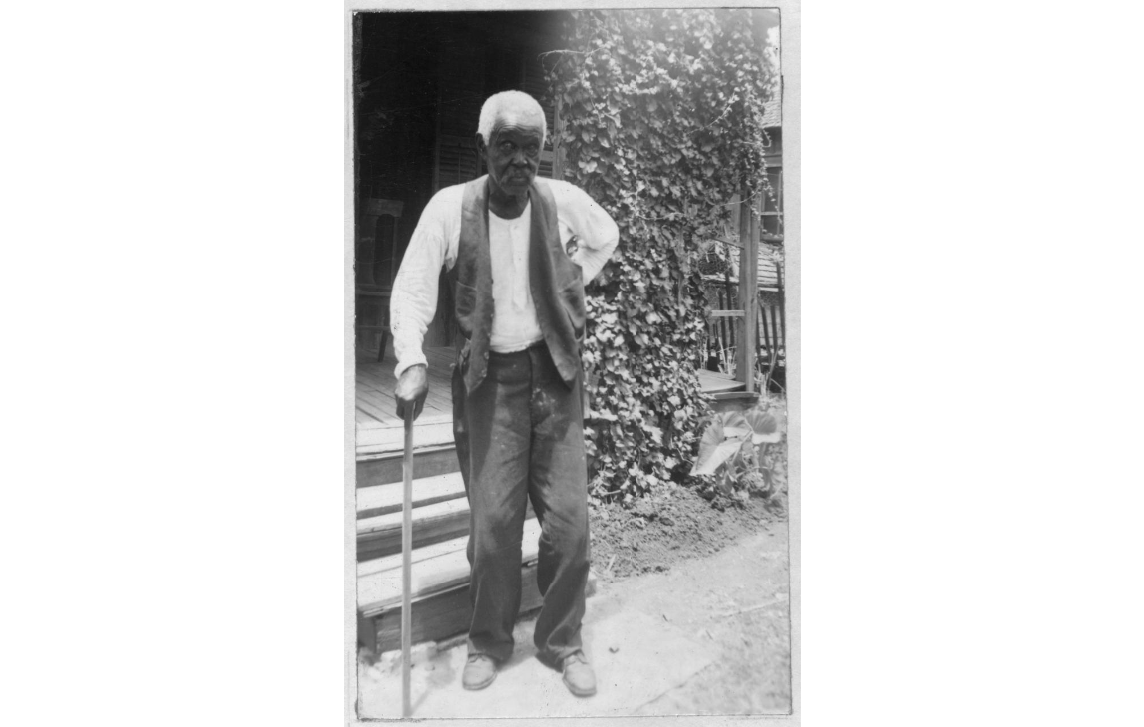

Felix Haywood was born a slave in Texas and freed as a child when the Emancipation Proclamation was approved

The 1860 census reported there were over 182,000 slaves in Texas and that enslaved Blacks comprised one-third of the state’s total population. But in Brazoria County and neighboring Wharton County, where the highest number of slaves in Texas lived, the percentage of Blacks making up the total population of these two counties was much higher.

In 1850 Brazoria County reported a white population of 1,329 and a slave population of 3,507. By 1860 the white population had increased to 2,027 and the number of slaves increased to 5,110, according to the East Texas Historical Journal, Volume 52, Issue 2, Article 6.

This East Texas Historical Journal report, researched by Matthew K. Hamilton, stated that as early as 1820, slaveholders across the South regarded the institution of slavery as a “necessary evil.” In 1860, just prior to the beginning of the Civil War, Brazoria County produced over 12,000 bales of cotton. The large plantations in Brazoria County, where the majority of Blacks in the county were forced to perform hard labor from sunup to sundown in the cotton and sugar fields, are where most slaves resided.

Seventy-two slaveholders who owned 20 or more slaves in Brazoria County accounted for 77 percent of the county total in 1860. Brazoria County boasted some of the largest landowners in all of Texas prior to the Civil War.

The Confederacy’s defeat resulted in most of these plantation owners losing the bulk of their fortunes. Author James L. Haley said that the Mills brothers—David and Robert—of Brazoria were devastated financially by the loss of their unpaid labor force. In Passionate Nation: The Epic History of Texas, Haley writes, “Between them before the war they were worth about $4 million, owning 800 slaves to work four plantations, and then baling, warehousing, and shipping their own cotton on their own steamboats. They lost it all, both finally going bankrupt in 1873; two of the plantations, fittingly, were in time incorporated into the system of state prison farms.”

Two Texas governors with ties to West Columbia are included in the many ex-slave narratives recorded between 1936 and 1938 by the Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration. Jeff Hamilton was interviewed September 16, 1937, for the Library of Congress Project, revealing that he was bought by Sam Houston, the first President of the Republic of Texas who lived briefly in Columbia in late 1836 and early 1837 when the first capitol of the new Republic of Texas was here.

Hamilton came to Texas as a slave when he was three years old. When he was about 12 his owner sold him to Sam Houston for $450 in Trinity County. “I hated to leave my mother and sisters,” Hamilton said. “The separation from them caused me to weep. General Sam Houston went in a store and bought me a new straw hat with a feather on the side, which I was very proud of.”

Jeff Hamilton said that Houston was serving in the Texas Congress at the time the Texas Revolutionary War hero purchased him. “I served him during the time he was governor. We moved from Austin when General Sam Houston served out his term as Governor to Chambers County on the Galveston Bay. We moved back to Huntsville, where (Houston) lived on the farm until he died. My work was to ‘tend to General Sam Houston and herd sheep. The General was very kind to me. He allowed me to live in the house with him and keep fires burning all night. I think General Sam Houston was one of the greatest men that ever lived.”

Jeff Hamilton, left, and Samuel Walker Houston, center, photographed at a Texas Centennial Celebration in Walker County in 1936. Jeff and Sam’s father had been slaves owned by the first president of the Republic of Texas, Sam Houston, an early Texas hero. Man on right unidentified.

Sam Houston served as the governor of Texas from 1859 to 1861. He died July 26, 1863.

Another ex-slave who contributed an interview to The Library of Congresss slave narratives program was Mandy Morrow. She worked as a cook in the Governor’s Mansion in Austin when James Stephen Hogg was the first governor of Texas who was actually born in the Lone Star State. Governor Hogg was governor of Texas from 1891 to 1895. After his term as governor ended, Hogg purchased the Martin Varner-Columbus Patton plantation near West Columbia in the early 1900s.

Mandy Morrow was born a slave near Georgetown, Texas, where Ben Baker had owned Mandy’s grandparents, parents, three brothers and one sister. She lived in Fort Worth and was about 80 years old when she was interviewed in the late 1930s.

“Mammy and my grandma cooks and powerful good and dey’s larnt me and dat how I came to be a cook,” she told the interviewer. “When surrender breaks all us stay with Massa for good, long spell. When pappy am ready to go for hisself, Massa gives him de team of mules and de team of oxen and some hawgs and one cow and some chickens. Dat give him de good start.”

She said she went to Austin about 20 years after gaining her freedom. “After I been dere ‘bout five years, Gov’ner James Stephen Hogg sends for me to be cook in de Mansion and dat de best cook job I’s ever had.”

Mandy said Governor Hogg “say I does wonders wit dat food and him proud for to have his friends eat it. I works for de Gov’ner till he wife die and den I’s quit, ‘cause I don’t want bossin’ by de housekeeper what don’t know much ‘bout cookin’.”

Many Blacks were enslaved laborers on the plantation outside West Columbia that had been owned by Martin Varner and Columbus Patton prior to the Civil War. Now the Varner-Hogg Plantation and the Levi Jordan Plantation near Brazoria and Sweeny are owned by the State of Texas and present exhibits that focus more on what slave life was like prior to emancipation than on the land owners.

In 2021 President Joe Biden signed into law the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act, turning what was once a mostly Texas celebration into a nationwide holiday.