![]()

By Tracy Gupton

Columbia Historical Museum

Discussions of the “early days” of the history of the West Columbia and East Columbia area of Brazoria County far too often begin with the introduction of Anglo settlers first stepping foot on the fertile grounds between the Brazos and San Bernard Rivers in the 1820s. However, the land was not unoccupied prior to Stephen F. Austin leading “The Old 300” American families from western Louisiana into what was then the southeastern portion of Mexico.

Famous names like Austin and Sam Houston are more frequently associated with early Columbia, Texas, due to our quaint little town’s place in Texas History as the first capitol of the new republic in 1836 and 1837. Less well-known names like Josiah Bell, Martin Varner, James Phelps and Brit Bailey come to mind if the topic of who the Columbia area’s earliest settlers were.

History failed to record the names of the many people who called this area home for centuries before the arrival of the white man. The indigenous inhabitants of a strip of Texas coastal inlets, marshes, and forests from Galveston Bay to Corpus Christi Bay were the Karankawa Indians. Former West Columbia High School teacher and coach James “Deacon” Creighton wrote in his 1975 book, “A Narrative History of Brazoria County, Texas,” that “the Karankawa Indians were by far the fiercest and most aggressive of all tribes in the Texas coastal plains” in the early 1820s.

“Because of their unceasing threat to life and property (of the white settlers), Austin on June 22, 1824, ordered five companies of militia recruited to make the colony safe,” wrote Creighton, who taught school in West Columbia in the 1920s and early 1930s. “Brazoria County was included in the jurisdiction of Captain Randall Jones (who the nearby community of Jones Creek is named after).”

Creighton said that James Brit Bailey (who Bailey’s Prairie between East Columbia and Angleton is named for) was first lieutenant of this militia. Reported failed attempts to get along with the “Kronks,” as the Anglo settlers often referred to the area’s natives, reached a boiling point when a number of Karankawa braves showed up at Brit Bailey’s store demanding to purchase ammunition, according to Creighton’s history of Brazoria County.

When fighting ultimately broke out between Bailey and other white settlers with the Karankawas, Captain Jones and over 20 other militia members pursued the fleeing “Kronks” toward their encampment “on a small tributary of the Bernard River” where, at about dawn, a violent confrontation commenced, resulting in the deaths of three Anglos and the retreat into the marsh grass by the Karankawas.

Stephen F. Austin reportedly wrote near the end of 1824 that “The Indians are now beginning to fear us, but we cannot for some time hope for complete peace with them.”

As the influx of more and more Anglo settlers into the Columbia area (both East Columbia and West Columbia were founded by Stephen F. Austin’s close associate, Josiah Hughes Bell, and his wife Mary in the 1820s) the threat of attack from the natives of the region grew less likely. Judge Thomas M. Duke, who participated in the raid on the Karankawa camp led by Captain Jones and Brit Bailey, wrote that in 1822 the Karankawa “count between 200 and 300 warriors,” Creighton wrote in his book, stating that by 1855, with the exception of perhaps a half dozen or so individuals living in the State of Tamaulipas, bordering Texas in Mexico, “the Karankawas were a lost tribe.”

History records numerous accounts of a combination of diseases spread by the white settlers that the Indians had no immunity for, and coming up on the losing end of far too many battles with the whites as the primary reason for the disappearance of the Karankawa from Brazoria County.

Author Robert A. Ricklis wrote, in his ecological study of cultural tradition of the Karankawa Indians (1996, University of Texas Press), that 18th Century documents “indicate the northernmost Karankawan group, the Cocos, living primarily around the mouth of the Colorado River and as far up the coast as the Brazos River.”

Ricklis writes that, “there is considerable archaeological evidence showing that Karankawan culture has prehistoric antecedents on the Texas coast,” and adds in his book that, “a Karankawan characteristic that repeatedly set them apart from neighboring Indian groups was their physical stature. It is clear that the Karankawas were unusually tall for Native Americans … and were noted for their strong and robust physiques.”

A recent article in Texas Highways magazine titled “We’re Still Here” reveals that the Karankawas did not become a “Lost Tribe” like Deacon Creighton wrote in his 1975 book on Brazoria County History. “The Karankawa are not extinct,” the 2022 magazine article states, “and almost everything you thought you knew about them is wrong.”

“Karankawa warriors were the stuff of nightmares” with “cane ornaments piercing their noses and nipples,” the Texas Highways story by John Nova Lomax starts off. “Reports of their savagery date to the accounts of French and Spanish explorers in the 17th and 18th centuries. The Karankawa were described as wearing breechcloths or nothing at all, revealing muscular bodies covered in tattoos and paint.”

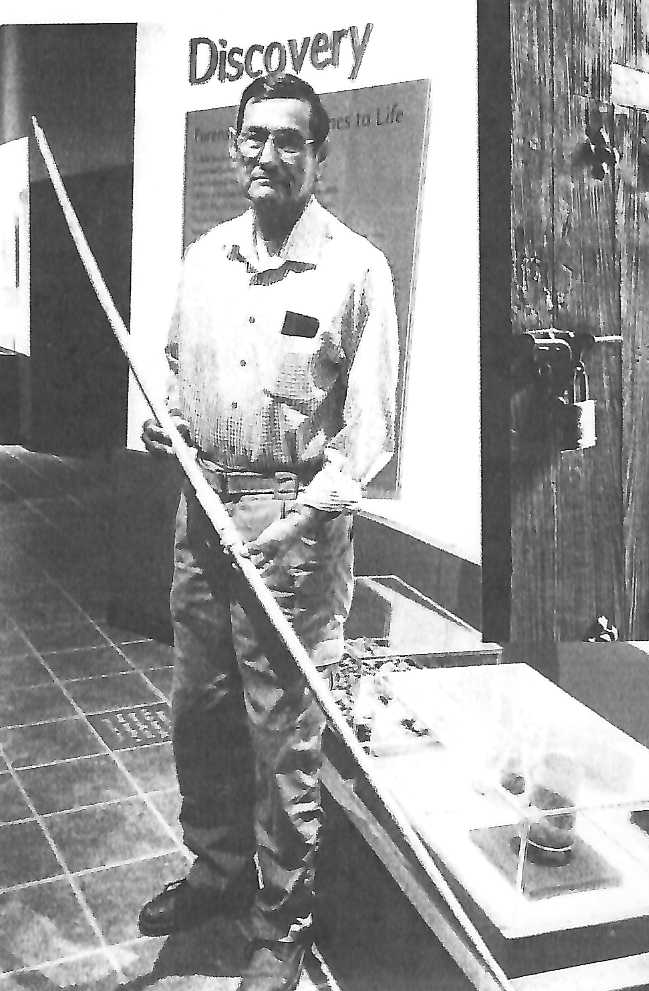

“The men were described as fleet of foot and powerful wrestlers,” Lomax writes. “They coated themselves in a poultice made of either shark oil or alligator grease, which warded off mosquitoes and also gave them a pungent aroma. Their red cedar longbows were almost as tall as they were, and their strings sent steel-tipped, goose-feather guided arrows hissing with unerring accuracy through the bodies of their prey and combatants alike.”

The Brownsville Herald published a profile in 2009 on Enrique Gonzalez Jr., a resident of Alamo, Texas, who claims to be a direct descendent of the Karankawa tribe. Gonzalez, a U.S. Army veteran, claims to have a Karankawa grandparent on both sides of his family.

The Brownsville Herald article revealed that Gonzalez grew up in El Gato, a Rio Grande Valley settlement on the Texas-Mexico border where his Karankawa ancestors fled after being driven first from the Texas coastal area where the tribe once thrived and then from more populated areas along the Rio Grande in Texas and Mexico. Hundreds of families across Texas and beyond have also surfaced as modern-day Karankawa or mixed Karankawa who all want to get the word out: “We’re still here.”

Karankawa descendent Enrique Gonzalez Jr. of Alamo, Texas, displays an heirloom fishing bow at the Museum of the Coastal Bend in Victoria

“Just like most folks grew up knowing that they were American, or maybe that they were Irish,” Chiara Sunshine Beaumont is quoted in Lomax’s story in Texas Highways magazine. “I grew up knowing that I was Karankawa. When I went to school and was learning about Native Americans, my mother would correct what I was being taught (about Karankawa Indians being vile and extinct).”

Horror stories of the Karankawa tribe being cannibals during and preceding the introduction of Anglo settlers into their region of coastal Texas in the 1820s and 1830s were most likely exaggerated. Robert Ricklis writes in his 1996 book on the Karankawa, “They had their traditional tribal enemies, on whom they may have waged war on a more or less regular basis. Enemies killed in battle were at times apparently subjected to cannibalism, although this was probably similar to the ritualistic practices found among other aboriginal groups and should not in any way be regarded as peculiar to Karankawan culture.”

Ricklis postulates in his book that by the 1840s, the Karankawas “had a population of 100 or so individuals. Survivors of the catastrophic depopulation of the 1820s through 1840s probably dispersed—most likely into northeastern Mexico—to become absorbed into other, still viable native populations.”