![]()

By Tracy Gupton

Columbia Historical Museum Board Member

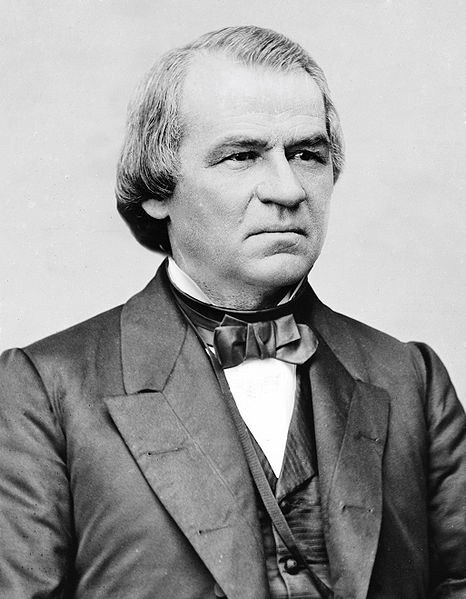

Just as conspiracy theories blossomed when Vice President Lyndon Johnson succeeded slain President John F. Kennedy in November 1963, rumors circulated in Brazoria County, Texas, when the brother of another U.S. President named Johnson died in late October of 1865. The 17th president of our great nation, Andrew Johnson, did not attend his older brother’s funeral in West Columbia – just known as Columbia in those days – but did get to enjoy a brief reunion with his sibling earlier the same year William Patterson Johnson passed away.

While John Wilkes Booth and Lee Harvey Oswald succeeded in etching their names in the annals of American History by assassinating Presidents Abraham Lincoln and JFK respectively, the killer of William Patterson Johnson was no mystery like Oswald’s guilt is still being questioned 59 years after President Kennedy’s assassination in Dallas.

William Patterson Johnson’s killer was William Patterson Johnson. At least it is certain that he accidentally shot himself while reportedly bird hunting in Velasco near the mouth of the Brazos River. But could the life of the sitting President’s older brother have been saved if physicians had made more of an effort to keep him alive?

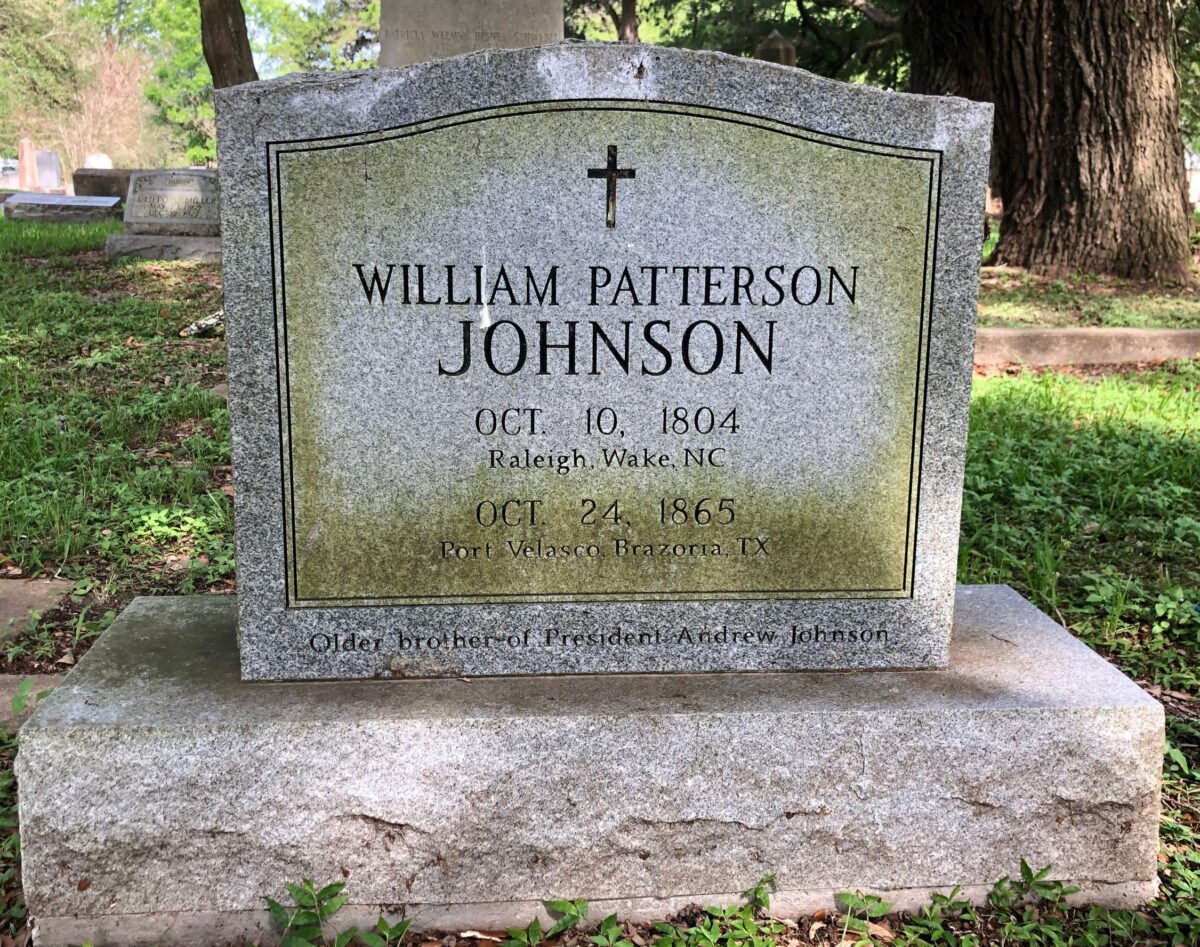

William was 61 when he drew his last breath on October 24, 1865. While stepping out of a boat on the banks of the Brazos River at Velasco (present day Freeport) on October 9, 1865, the shotgun Johnson was using caught on a gunnel of the boat and discharged its full load of pellets into his arm.

The small community of Velasco had no doctors available to treat the President’s brother, so he was taken to Brazoria to have his serious wounds tended to. Research of the incident reveals that a Dr. Stevens eventually treated William Johnson, but he had lost a great deal of blood and gangrene had set into the wounded arm.

John Adriance, a Columbia merchant and local civic leader, recalled that he was traveling with Colonel J.C. DeGress, provost marshal general of the Eastern District of Texas, elsewhere in Brazoria County when a messenger informed them of William Johnson’s unfortunate accident at Velasco. Colonel DeGress ordered the Provost Marshal at Columbia to send a surgeon accompanied by Union soldiers to Brazoria to treat the President’s brother.

To set the stage for this grisly event, the Civil War had only recently reached its bloody conclusion, Andrew Johnson had taken over as the nation’s President after Lincoln was assassinated, and Texans were adjusting to reconstruction and occupation of the region by Northern enforcers. Dr. O.H. Seeds of Columbia is reportedly the surgeon who amputated William Johnson’s wounded arm due to the bad shape the injured limb was in when the physician reached him.

There are conflicting reports as to whether Johnson was in Brazoria or Columbia when he finally died of gangrene following the amputation, but his funeral and burial occurred in what today is known as West Columbia. An impressive headstone marks the site of his burial at historical Columbia Cemetery.

An article published in the Tennessee Historical Quarterly stated that President Johnson, when informed of his older brother’s passing in Brazoria County, apparently accepted the explanation that nothing more could have been done to save William’s life.

Andrew and William Johnson were both born in Raleigh, North Carolina (William was four years older). Andrew Johnson ended up in Greeneville, Tennessee, where he eventually served in the state senate and house of representatives. In 1862 President Lincoln appointed him Military Governor of Tennessee and in 1864 Republicans nominated Andrew Johnson to replace Hannibal Hamlin for Lincoln’s second term as vice president.

This transition in vice presidents during President Lincoln’s tenure in the White House created the opportunity for Andrew Johnson to become President. William Johnson, a skilled carpenter who married Sarah Giddings McDonough in 1832 in Raleigh before moving to Greenville, Tennessee, eventually went to work for the J.H. Dance and Brothers manufacturing business in East Columbia building houses and making gristmills and revolvers for the Confederate Army during the Civil War.

President Johnson appointed his brother William to the position of Collector of the Port of Velasco in mid-1865. The work he was doing at the mouth of the Brazos River put William Johnson at this location where, a few months later, his accidental shooting resulted in his death.

He and his wife Sarah had six sons, Nathan, Devolco, Jacob, Andrew, James and William Jr., and four daughters, Elizabeth, Laura, Jane and Olive.

While the President may have accepted the explanation surrounding his brother’s death, some of William Johnson’s children claimed negligence on the part of Brazoria County physicians in failing to treat their wounded father properly. A January 1866 letter to the editor published in The New York Times refuted alleged claims made in an earlier letter to the New York City newspaper by sons of William that “rebel surgeons of the vicinity refused to render any assistance, on the grounds that Mr. Johnson was a brother of the President.”

The author of the follow-up letter to the editor claimed he was in Columbia at the time of William Johnson’s death and said that Johnson’s sons were not in Texas when their father died. “There was every mark of respect shown him by the people attending his funeral (at Columbia Cemetery),” the letter’s writer claimed.

Research also reveals that William and Andrew Johnson had not seen each other “except for 24 hours at their mother’s deathbed in February 1856 in Tennessee” since 1839. Another New York Times story published in August 1865 reported that William Johnson visited President Johnson in Washington D.C. for a brief family reunion earlier that summer. Voters in Tennessee returned former President Andrew Johnson to the Senate in 1875, a decade after the death of his brother William. Andrew Johnson died of a stroke July 31, 1875, in Elizabethton, Tennessee, at the age of 66.