![]()

By Tracy Gupton

Open for tours since 2009, the Columbia Historical Museum’s prized Rosenwald School is now in its 15th year of being available to visitors of the museum as part of their immersion into a world long since gone. The museum at 247 East Brazos Avenue in downtown West Columbia is chock full of artifacts and displays highlighting the history of the small Brazoria County community that once was the first capital of the Republic of Texas in 1836-37.

The Rosenwald School is located directly behind the museum, which formerly was the First Capitol Bank building and briefly served as West Columbia’s public library. The schoolhouse is at the corner of Broad Street and Clay Street. February is Black History Month and the former school building for Black children of the East Columbia area will be the site of several events the museum has planned for this month.

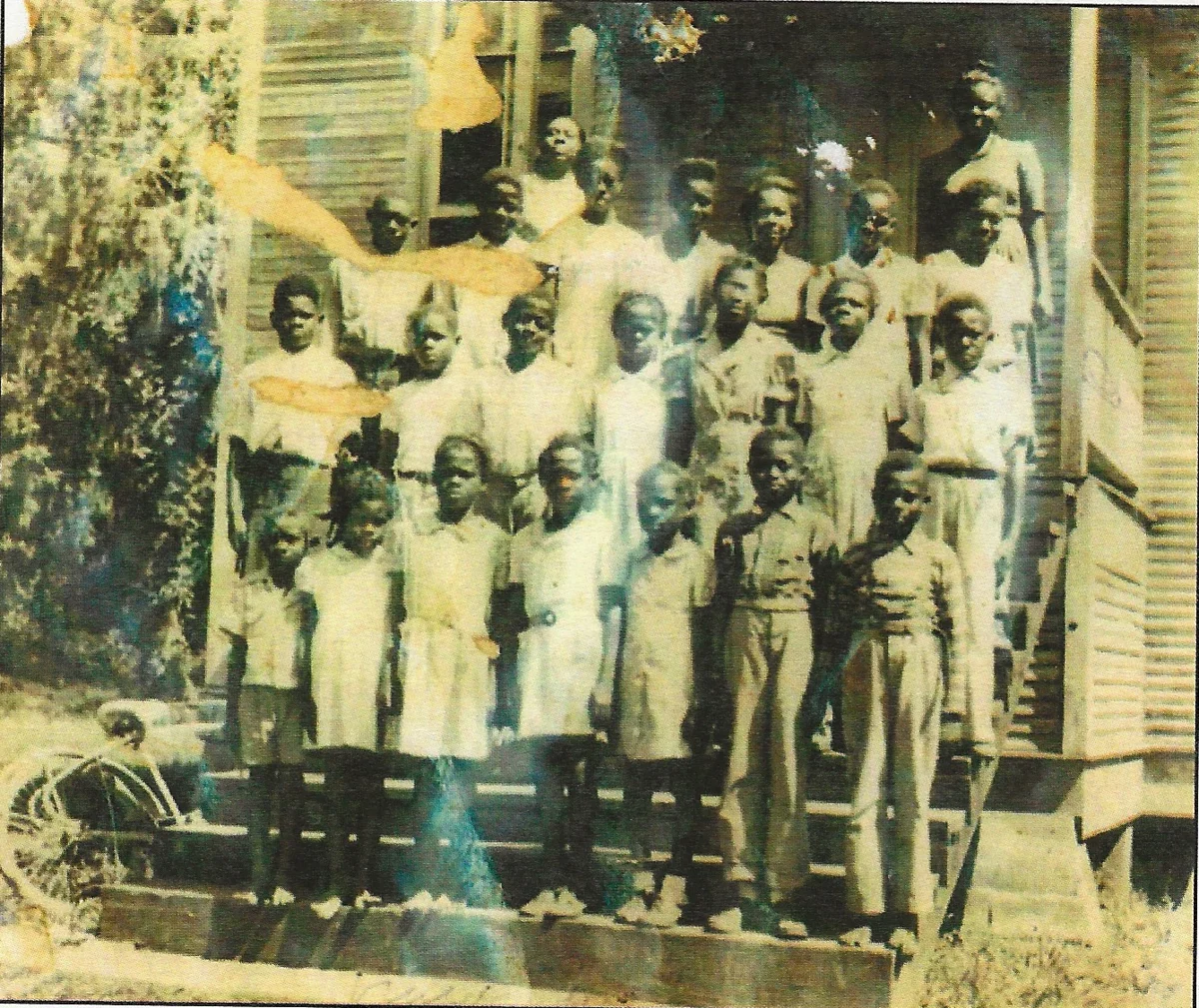

Columbia Historical Museum Curator Michael Bailey said alumni of the old school are being invited to take part in a special reunion planned for the final Saturday in February. Attempts are presently being made to contact the few former students still living in the area to let them know about the February 24th event in hopes they will be able to attend and take part in the Rosenwald School reunion.

That event, like all of the Black History Month programs the museum has planned each Saturday this month, will begin at 10 a.m. and end at 2 p.m. every Saturday in February. And each Saturday program is free and open for the public to attend. Holy Trinity Church’s choir, under the direction of pastor Reverend Anthony Hall, will be performing this Saturday, February 10th, at the Rosenwald School. And there will be an open house the following Saturday, February 17th, at the old schoolhouse for anyone interested in touring the building and learning more about its history.

The Columbia Rosenwald School was built in 1921, and for nearly 30 years served as the center of education for the Black children living in the East Columbia area. It was one of 5,338 Rosenwald schools constructed throughout the South between 1913 and 1932. In the state of Texas alone there were 537 Rosenwald schools built. The only ones still standing today are in Cedar Creek (built in 1922), Lockhart (built in 1923), Seguin (built in 1924), Linden (built in 1925) and Dayton (built in 1927), along with West Columbia’s historic school building.

Former Brazoria County News editor Teena Maenza wrote in her 2006 publication, The Columbia Rosenwald School, that “only around 40 still exist” in the nation. She wrote that most Black children in the West Columbia/East Columbia area were educated in churches or lodge halls, “wherever space could be found.”

“Despite the fact that the Civil War had been over for four decades, there had been no consistent effort made to educate black children, especially in the small rural communities,” the late Teena Maenza wrote. “The responsibility for education fell to the churches, and the quality varied widely.”

In giving tours of the West Columbia Rosenwald School, current Columbia Historical Museum President Naomi Smith explains to visitors that the philanthropic endeavor spearheaded by Tuskegee Institute founder Booker T. Washington and former Sears, Roebuck and Company President Julius Rosenwald required local community involvement in order to acquire the financial assistance from Rosenwald and Washington.

“Rosenwald believed that any community desiring a school had to be willing to contribute matching funds,” Maenza wrote. “Not only did the black segment of the community have to donate, but the white segment as well, and the local school board had to take ownership and oversee the education of the children.”

A writeup on Rosenwald Schools on Wikipedia states that, “The Rosenwald-Washington model required the buy-in of African American communities as well as the support of white governing bodies. Black communities raised more than $4.7 million to aid in construction, plus often donating land and labor. Research has found that the Rosenwald program accounts for a sizable portion of the educational gains of rural Southern black persons during this period.”

Maenza wrote that the Rosenwald-Washington fund contributed one-third and the local communities had to come up with the additional two-thirds of the total amount needed to build these schools for Black children.

Naomi Smith tells visitors to the West Columbia Rosenwald School that all of the schools were built so that the classrooms received sunlight through the large glass windows on the proper side of the school, and the students’ desks were arranged with the larger windows on their left side so that no shadows would be cast on their work. The smaller windows on the western side are placed higher on the wall, situated above the chalk boards.

“The Columbia Rosenwald School sits on a pier and beam foundation,” Maenza wrote in her booklet that is still being handed out to visitors today. “It was originally five feet off the ground due to its close proximity to the Brazos River when it was constructed in East Columbia.”

Former Charlie Brown High School coach Morris Richardson, who was an original member of the Columbia Historical Museum Board of Directors, told his fellow board members that he had taught in a Rosenwald school in the early days of his teaching career and that he believed a building outside of West Columbia being used as a hay barn had formerly been a Rosenwald school. Through a little research it was discovered that the hay barn actually was the old school house for Black children that had been moved from its original location in East Columbia to a pasture just south of where the school had been originally built.

Through the dedicated efforts of Coach Richardson and his wife Lois, Emma Womack and her son, Bill Womack, and others, the museum board was able to purchase the hay barn/school house from the Jimmy Phillips estate through Alex Weems in 2002. After persuading the West Columbia City Council to allow the museum board to place the Rosenwald School on the lot directly behind the museum, with the front door of the school facing Clay Street, the real work began.

Maenza writes that, “After a decade of hard work and dedication on the part of the Columbia Historical Museum and the community, the Columbia Rosenwald School opened to the public on October 24, 2009 as an interactive space giving children the opportunity to experience what attending school was like in the 1920s.”

Smith shares credit for achieving this worthwhile endeavor with several corporate sponsors–such as the Meadows Foundation, the Lowe’s Charitable and Educational Foundation, and the National Trust for Historic Preservation–and alumni of the original East Columbia school who volunteered to pitch in.

Efforts on the part of the museum board were eventually successful to obtain a Texas Historical Commission subject marker that was placed in front of the Columbia Rosenwald School in December of 2007.

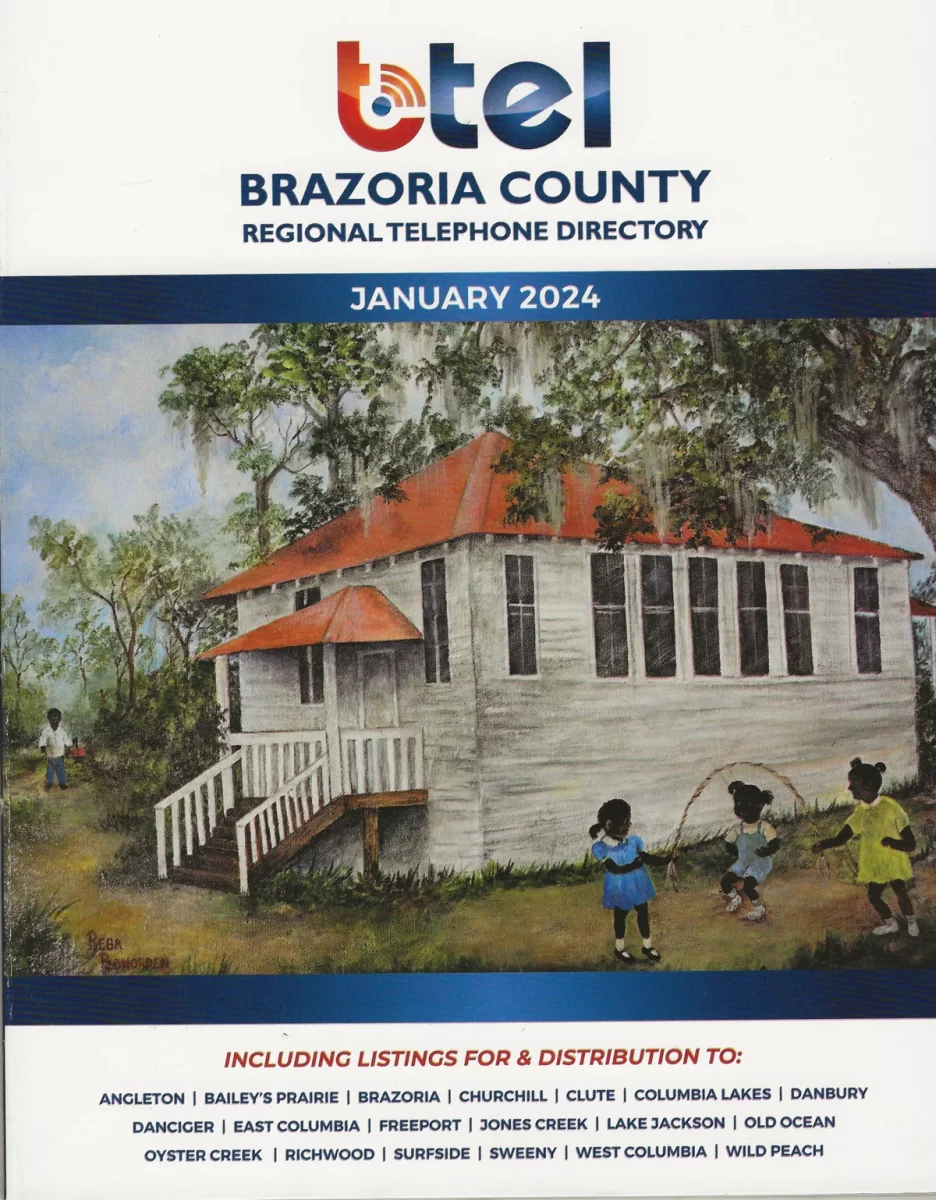

The January 2024 edition of btel’s Brazoria County Regional Telephone Directory sports a painting of the old East Columbia Rosenwald School on its cover. Naomi Smith wrote the informative story about the history of this prize display showcase at the Columbia Historical Museum for the btel phone book. In her writeup, Smith says that the school for Black children was used in East Columbia from 1921 to 1948.

In her writeup for the btel phone book, Smith says that the East Columbia school was one of five Rosenwald schools constructed in Brazoria County. “It’s the only (Rosenwald) school left standing in Brazoria County and is one of only five remaining in Texas today,” she said.

“All (Rosenwald) schools were to be placed with front doors facing north,” Smith wrote. “This allowed the sun to shine on the students’ shoulders, and not on their faces.”

Smith said that the Columbia Rosenwald School is “the only one currently used as an interpretive center with period desks, the original teacher’s chair, a replica of what was used as a desk for the teacher, and one desk from its time of glory. Eighty-five percent of the material in the school is original.”

She said that the land for the East Columbia Rosenwald school was donated by former slave Charlie Brown of West Columbia, “who never learned to read or write but amassed a fortune in land and money. When Charlie Brown died in 1921, he was the fifth wealthiest man in Texas.”

For further information about the Columbia Historical Museum, its Rosenwald School, or the events planned for recognition of Black History Month throughout February, contact the museum at (979) 345-6125.