![]()

The great monument, a huge obelisk, that can be seen miles away from the site near present day La Porte, commemorates the San Jacinto battlefield. On this day, April 21st, in 1836, the Texan army led by General Sam Houston savored the sweet taste of victory over the Mexican military force at San Jacinto.

With the victory came the spoils. Mexican President Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna was captured at San Jacinto and eventually granted the Texas Anglo settlers their independence from Mexican rule. And the rest, as the saying goes, is history!

Author James W. Pohl, who earned his Ph.D. in history from the University of Texas at Austin, wrote in his 1989 book, The Battle of San Jacinto, “Remarkably, the Mexicans were completely unprepared for the assault” by the Texas volunteers that day 187 years ago. “Without adequate security, some dozed in the late afternoon sun, some chatted, and others ate. It was Colonel Pedro Delgado who seems first to have noticed the threat. Quickly a bugle trumpeted a call to stations … It still had not registered that the outnumbered Texans were actually assaulting their position.”

Sam Houston, who would later that same year be sworn in as the first president of the new Republic of Texas at Columbia, ordered the assault and drew his sword, motioning the Texas troops forward. “They emerged from the timber line, each of the large units in column and the soldiers at trail arms and in line,” Pohl wrote in his book. “After covering roughly half the distance in this fashion, the units fanned to produce a linear formation consisting of two lines that stretched perhaps 900 yards. At this time the soldiers were ordered to raise their weapons to the port position.

“The Texans moved swiftly across the field. As the adrenaline pumped through the Texans, the quickstep deteriorated. Soon the men broke into a trot, and the parallel lines sloppily merged into one great mass. Sam Houston, astride his great white stallion, Saracen, about 20 yards forward of the front ranks, knew that he had little control over these frenzied men; but he was able to stop them long enough for one standing volley to be fired against the enemy lines at a distance of 60 to 70 yards. Some of the Texans had time to reload and refire, but by that time all semblance of linear order had disappeared and a general melee began.”

Dr. Pohl was a former president of the Texas State Historical Association and professor of history at Texas State University in San Marcos. He describes what led to the Texans victory at San Jacinto in his book:

“For the next 15 minutes, blood and carnage ruled. No one was exempt. Even Houston had two horses shot from under him, including Saracen, and was wounded. With cries of “Remember the Alamo!” and “Remember Goliad!” the bloody-eyed Texans killed as many as they could. In an attempt to escape the mounting fury, some of Santa Anna’s troops, mustering the best English at their disposal, responded in pathetic terror, “Me no Alamo! Me no Goliad!” In some cases, their plaintive appeals may have been true, for many of the men were new replacements.”

General Houston’s report of the historic battle at San Jacinto revealed that the actual battle ended after about 18 minutes, “but the killing went on for more than an hour,” Pohl wrote. The Texans had won!

Among the nearly 800 Texas volunteer soldiers who took part in the April 21, 1836, Battle of San Jacinto was 28-year-old Nathaniel C. Hazen. He served as a private in Captain William H. Patton’s company at San Jacinto after having escaped execution at Goliad on March 27th. Hazen is buried at Columbia Cemetery in West Columbia. He died in Columbia the same day as Stephen F. Austin on December 27, 1836.

A Texas historical marker at Columbia Cemetery was dedicated in 1936 near the grave of Nathaniel Hazen who escaped the Goliad firing squads to participate in the Battle of San Jacinto on April 21, 1836, under Sam Houston

A Telegraph and Texas Register newspaper story published in Columbia January 11, 1837, revealed that Hazen had served with valor in the Texas army between January 16 and November 10, 1836. He fought with Colonel James W. Fannin’s regiment March 19, 1836, near Goliad and managed to escape the Mexican firing squads a week later at Goliad, the newspaper story said. In 1936 a state historical marker was placed at Columbia Cemetery honoring Nathaniel C. Hazen for his bravery.

Santa Anna was captured the following day after the Texans victory at San Jacinto. The Mexican president had left his horse and had moved into the marsh on foot in an attempt to avoid capture. After spending the night in the reeds and grass of the nearby marsh, Santa Anna exchanged his general’s impressive uniform for some shabby clothing he found in a slave’s cabin. But when he was greeted with cries of “El Presidente!” from his fellow captives when Santa Anna was captured and returned to the Texans’ camp, he was taken before the wounded Sam Houston.

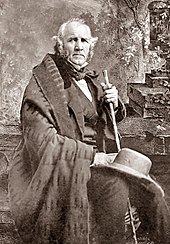

Sam Houston, the first president of the Republic of Texas, was the hero of the Texan victory at San Jacinto

Dr. Pohl wrote in his book that “Santa Anna demanded the courtesy he had denied others at the Alamo and Goliad – that he be treated honorably as a prisoner of war. He was, by that time, encircled by wrathful Texans, many of whom wanted his death. Santa Anna visibly trembled in anticipation of his fate, but he need not have worried – Sam Houston had other plans for him. Despite the wishes of some of his more outspoken men, Houston had no intention of executing his bloody-handed prisoner. Apart from his natural unwillingness to kill a helpless man, he knew something else – Santa Anna was worth much more to Texas alive than dead. This wisdom was attested to by the Treaties of Velasco signed by President Burnet and President Santa Anna less than a month after the battle of San Jacinto. That document stated that hostilities would cease and never be renewed, that Mexican troops would be removed from Texas soil, and that the Rio Grande would mark the boundary between the Republic of Texas and Mexico.”

President Santa Anna would serve several months in confinement near West Columbia following his capture at the Battle of San Jacinto. He remained a prisoner of the Texan army, first at what today is the Varner-Hogg State Park, then later at the Orozimbo Plantation on the Brazos River near East Columbia.

As Texans celebrate another anniversary of the Battle of San Jacinto this weekend, it is only fitting to take to heart the words inscribed on the San Jacinto Monument near Houston: “Measured by its results, San Jacinto was one of the decisive battles of the world. The freedom of Texas from Mexico won here led to annexation and to the Mexican War, resulting in the acquisition by the United States of the states of Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, California, Utah, and parts of Colorado, Wyoming, Kansas, and Oklahoma. Almost one-third of the present area of the American nation, nearly a million square miles, changed sovereignty.”