![]()

By Christina M. DeWitt

Columbia Historical Museum Board Member

Since I was a child, I’ve always been a darker shade from others. One of my first memories was visiting my great grandmother’s house in Oklahoma. She lived in a small town down the road from the Cherokee tribe. Her house was next door to a baseball field where the tribe played ball frequently. I loved to watch but was never allowed to go outside with them. As I got older, I asked Mom why she wouldn’t let me go out. Her response shocked me. She said, “I would never let you go play, because I was afraid the Indians would take you, and I would have to go through the tribal council to get you back!”

As I think about it now, it’s kind of funny. I’ve always been dark!

However, as an adult, I wanted to know exactly how much Indian blood I have and to which tribe I am affiliated. I’ve hit several roadblocks, the biggest being that because my great-great grandmother married a white man (outside the council), records seem to halt there.

So because of my interest in native Americans, I will take you in a slightly different direction looking at the rich history of Texas. It is also important that we look into the settlers who both help, and hurt Stephen F. Austin, and his colony, as they made their embark on the new territory of Texas.

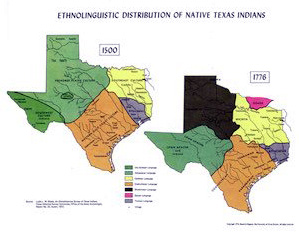

There were many different tribes in Texas: Apache, Mayeye, Tonkowa, Wichita, Rio Grande Jumano, Cherokee, Karankawa and others. The Karankawa is the most well known on the Gulf Coast and stretched from Corpus Christi to Galveston.

I would be remiss, if I tried to sit here and take away how integral Stephen F. Austin, was with helping the Indians. He “conducted relations with the Indian tribal council, and chiefs.” Austin helped many Indians by issuing passports, and letters of recommendations to friendly Indians. He did so, to help identify them, and attest to their tribal affiliation. (Belfiglio) This is just one of the reasons why I admire the work Stephen F. Austin put toward the natives, and preserving their affiliation to their native tribes.

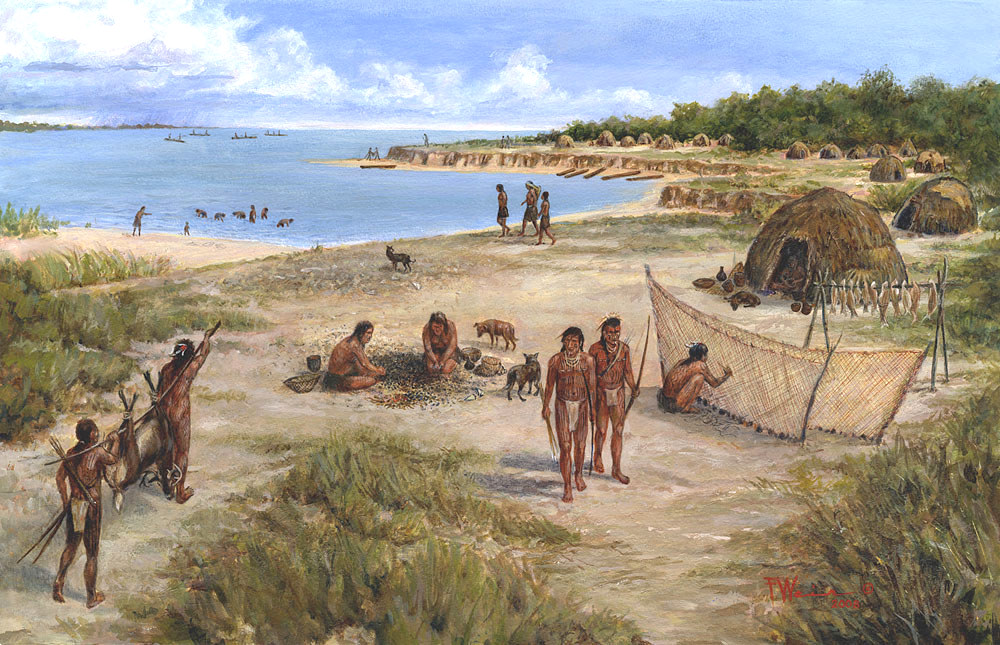

The “Karankawa Indians became the accepted designation for several groups of coastal people who shared a common language and culture.”

Many of those groups include: Carancahuas, Coapites, Cocos, Cujanes and Copanes. All uniquely bonded by speaking the same language known as Karankawa. “The significance of the name has not been definitely established although it is generally believed to mean “dog-lover” or “dog-raiser”. This is believed, mostly because they were known for having dogs.

My earliest memory of learning about the Karankawa Indians, was learning and being mesmerized by their mode of transportation. The Karankawa would take the trunk of a tree and hollow it out to form a canoe. Oh, how I would’ve loved to see them navigate one of those up and down the Gulf Coast. Their weapons were mostly bows and arrows, made from red cedar.

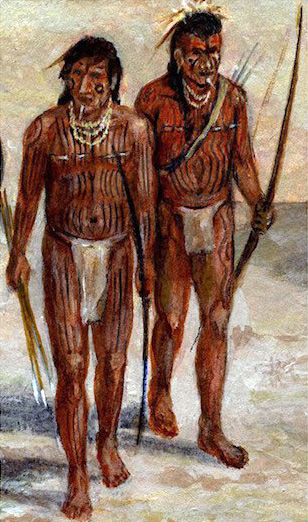

Because the Karankawa controlled most of Texas’ shallow bays and coastlines, they were also able to acquire guns from shipwrecks and they raided passing vessels. Known for their distinctive appearance, it was easy to know which tribe they were affiliated with.

The Karankawa were quite nomadic in small groups. This nomadic life-style, however, did not stop them from calling in reinforcements if needed. “A well-developed system of smoke signals enabled them to come together for social events, war-fare, or other purposes”.

War had to become part of their life due to the ever-changing environment of Mexico and European settlers, and, in fact, there is evidence indicating the tribe “practiced ceremonial cannibalism prior to the eighteenth-century that involved eating the flesh of their traditional enemies.” That custom was considered by the Karankawa as “the ultimate revenge or magical means of capturing the enemies’ courage.” It was this justification that the Anglo-Americans used when they decided to annihilate the tribe.

We can learn many things from the Indian cultures: one being, people fear what they do not know. Maybe we can all learn from the differences each has, and, instead of using it to destroy, we use it to edify and unite mankind.

Sources:

Belfiglio, Valentine J. (1993) “The Indian Policy of Stephen F. Austin,” East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 31: Iss. 2, Article 6. https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol31/iss2/

LaVere, David. The Texas Indians. College Station, Texas. Texas A&M University Press. 2013.