![]()

By Tracy Gupton

As Texian soldiers routed General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna’s Mexican troops at the decisive Battle of San Jacinto in April 1836, celebratory shouts of “Remember the Alamo” and “Remember Goliad” rained down on the fallen and fleeing Mexicans.

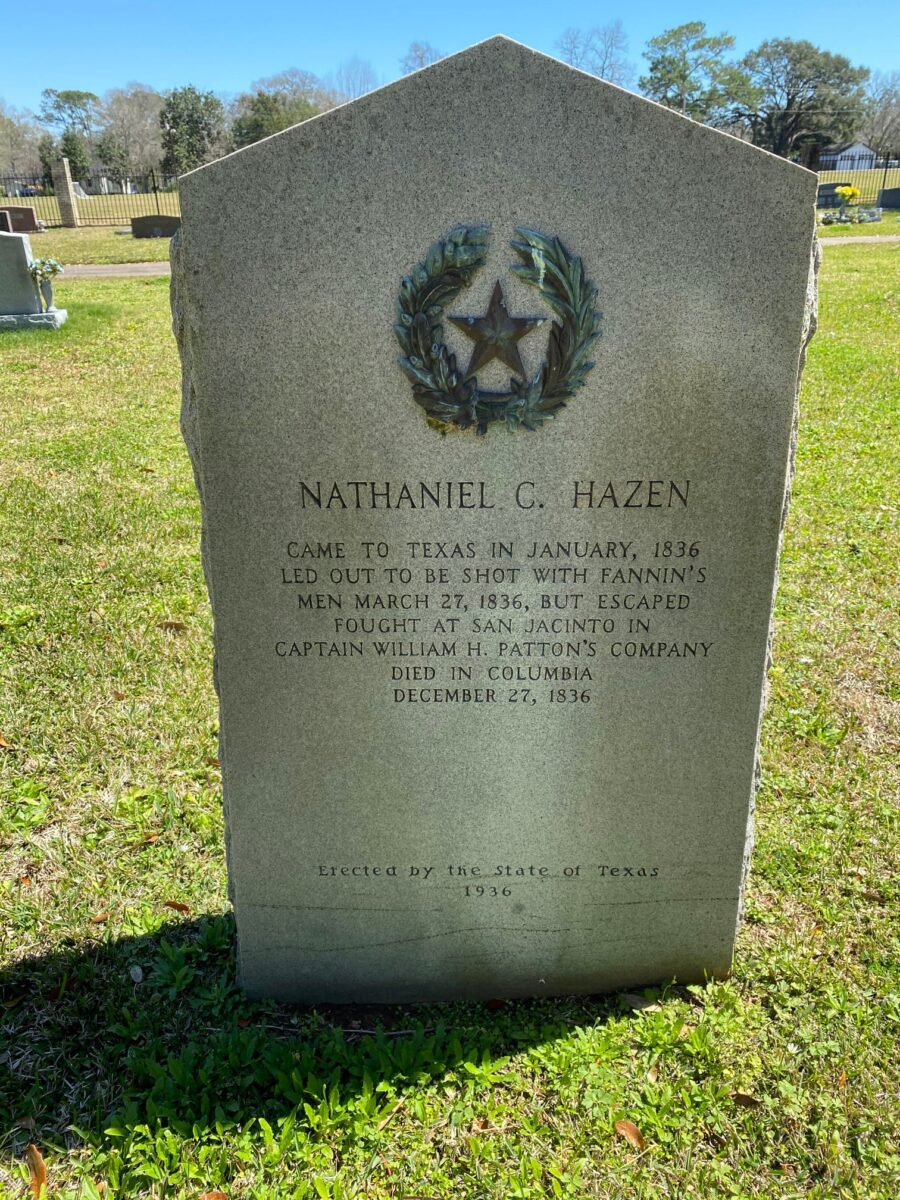

One of those soldiers shouting victory is buried in the Old Columbia Cemetery. Private Nathaniel C. Hazen survived the firing squads at Goliad and lived to fight the Battle of San Jacinto.

Hazen was able to escape when the bloodbath at Goliad began, and he found his way to General Sam Houston’s camp. He lived only until the end of the year, dying the same day as the “Father of Texas,” Stephen Fuller Austin, on December 27, 1836.

Hazen was buried at Josiah and Mary Bell’s plantation at Columbia at the age of 28. The state of Texas erected a historical marker in Columbia Cemetery in memory of Hazen’s bravery in 1936 during Texas’s centennial. The San Jacinto Museum also lists an entry about Hazen’s participation in the battles of San Jacinto and Goliad. (https://www.sanjacinto-museum.org/Library/Veteran_Bios/Bio_page/?id=397&army=Texian)

Hazen and his fellow ragtag soldiers, led by General Sam Houston, sought revenge at San Jacinto, showing the defeated Mexican soldiers the same lack of mercy that their leader, Mexican President Santa Anna, had dealt out to Texian prisoners of war, which Hazen well remembered.

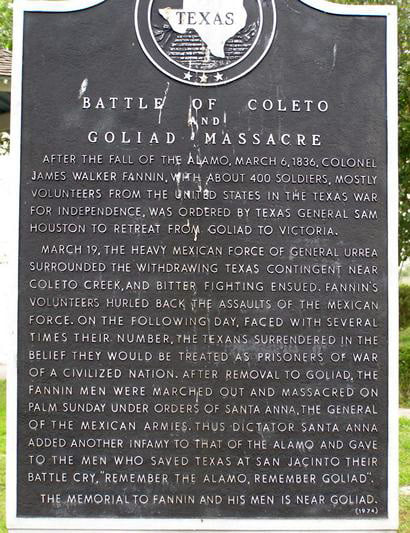

Three weeks to the day after the fall of the Alamo on March 6, 1836, Santa Anna ordered the mass executions of all of the Texian soldiers captured at the Battle of Coleto Creek on Palm Sunday, March 27th, at Goliad. Colonel James Walker Fannin, who owned the Fannin-Mims plantation near Sportsman’s Span bridge near Brazoria, was the commanding officer of an estimated 400-man force of Texian soldiers manning Fort Presidio La Bahia near Goliad at the time the Alamo was overtaken by Santa Anna’s troops.

Houston ordered Colonel Fannin to evacuate the fort at Goliad on March 14, 1836, the same day Mexican General Jose de Urrea’s troops surrounded Colonel William Ward’s 200 Texian soldiers and defeated them in a bloody battle between the Lavaca and Navidad rivers.

By disobeying General Houston’s command to retreat toward Victoria when he was instructed, Colonel Fannin’s delay in leaving Fort Presidio La Bahia until the morning of March 19th had a deadly outcome. Author William C. Davis, in his book “Lone Star Rising” (Free Press, 2004), said that Fannin intended to leave Goliad on March 18th “but when heavy fog set in after dark he decided to wait until the next morning,” a delay that enabled General Urrea’s troops to overtake the Texians in an open meadow around midday on March 19th.

Author Randolph B. Campbell wrote in his book “Gone to Texas” (Oxford University Press, 2003), in addressing Colonel Fannin’s decision to have his men rest for over an hour mid-morning on March 19th for the oxen pulling the Texians’ cannons and wagons filled with muskets and ammunition to graze, “Some of Fannin’s men, aware of what the Mexican cavalry could do to them in the open, begged Fannin to move in to the cover of trees along Coleto Creek,” but their commander refused.

When Urrea’s advance riders spotted the resting Texians, Colonel Fannin had his men form a hollow square with cannons set up at each corner. The ensuing battle lasted the rest of the afternoon. Urrea’s onslaught ceased at dark. Author T.R. Fehrenbach wrote in his book “Lone Star” (Da Capo Press, 2000), “Fannin enveloped by Urrea’s vastly superior force, was unnerved all night by the cries of his suffering wounded, begging for water.”

The next morning, Fannin sent up a white flag after the battle resumed, and the outnumbered Texians had taken some 60 casualties. Some historians believe Fannin was given good reason from his negotiations with Urrea and other Mexican officers to believe his men would be spared upon surrender and allowed to return to Louisiana.

Those Texians who had not been killed on the battlefield were marched back to Goliad as prisoners and kept under guard for several days in the presidio at La Bahia. General Urrea reportedly campaigned to save Fannin’s men’s lives, but Santa Anna made some 400 martyrs for the Texas cause when he ordered the captives be executed. The Goliad Massacre claimed the lives of twice as many Texas rebels as at the fall of the Alamo.

Twenty-eight Texians are believed to have escaped the massacre, including Hazen. One source has the number killed at 342; another source lists more than 425 executed. Colonel Fannin was the last of the group to face the firing squad.

The State of Texas erected a historical monument at Columbia Cemetery in 1936, 100 years after the death of Nathaniel C. Hazen in Columbia, Texas, in honor of the soldier who died at 28 on December 27, 1836, following his involvement in both the battles of Coleto Creek under Colonel James Fannin and at San Jacinto under the leadership of Sam Houston. Hazen, who escaped the massacre at Goliad on March 27th, had come to Texas in January 1836 but sadly died less than a week before New Year’s Day 1837.

Are their any testimonials documented that Hazen left behind? I was wondering how he escaped the Goliad Massacre.