![]()

By Tracy Gupton

Columbia Historical Museum

Fear preceded panic when I suddenly found the soles of my feet no longer touching the sandy bottom of the Gulf. I was just a little kid in the early 1960s, splashing around in the surf at either Bryan or Surfside beaches near Freeport. My older brother Cody was nearby, and our cousin “Little Hank” had been swimming in the vicinity of where I was when my bouncing up and down in the waves quickly switched from lots of fun to my swallowing lots of salt water.

The outcome of this scary ordeal is obvious. I survived to reach my present age of 66 and lived to write this story. The scene was a family gathering at the beach. The adults were gathered in and around a rented beach house while Gupton children were enjoying the summer sunshine while frolicking in the surf.

My swimming skills were minimal at my young age. I recall kicking my legs frantically, trying to find sand under my toes while bobbing above and below the surface of the water. Attempts to scream for help failed due to the salt water I kept swallowing. Suddenly my eyes focused on my uncle wading out to get me. “Little Hank’s” father, “Uncle Hank,” my Dad’s brother, observed my situation from the beach and quickly covered the short distance to where I was struggling to avoid drowning.

The other kids swimming not too far from me did not even notice what was happening. Thankfully, my uncle pulled me out of the ocean and carried me on his broad shoulders back to the beach where nothing was mentioned to my parents about my ordeal of stepping off a sandbar into an area where the water was way over my head.

I survived while many others, including Abe Jones and J.D. Amboree, did not. They did not live to tell their stories.

My mother, Verna Gupton, used to tell me when I was a teenager of her scary recurring nightmare of driving a car off a bridge and not being able to extricate herself from the rapidly sinking automobile. She said she always woke up from her dream in a panic, her drowning experience not being real. But for my childhood friends J.D. Amboree, Steve Denson and John McKinney, the reality of their situations proved fatal.

John D. Amboree Jr., who graduated from Columbia High School in 1974, the year before Steve Denson and I, was a talented running back for the Roughnecks football team. The same surf that nearly snuffed out my young life in the early 1960s claimed my friend J.D. on Sept. 5, 1988. He was only 32-years old.

Claude Grady “Abe” Jones was even younger when he drowned at Surfside Beach the night of May 22, 1948. The longtime West Columbian was 28. Born in Vinton, Louisiana, in 1919, Abe’s family moved to West Columbia in 1922. He had spent five years in the U.S. Army during World War II and had achieved the rank of staff sergeant before returning home after the war.

He had been a member of the West Columbia Volunteer Fire Department but had recently moved to Clute prior to his drowning when he went to work in the chlorine department at Dow Chemical. And even though Abe Jones was associated with the Clute Fire Department at the time of his death, he had joined a group of West Columbia fire fighters at Surfside Beach for fishing and what everyone involved hoped would be an enjoyable gathering. Boy were they wrong!

About 20 good friends from West Columbia and Sweeny were fishing together and having a good time. Nine men were out in the surf seining with large nets late at night. A newspaper report in The Freeport Facts stated that the men had stretched their 300-foot net out about 20 yards from the coast “when they were caught in the backwash, which carried Jones out to sea. Six of the party got back to shore.”

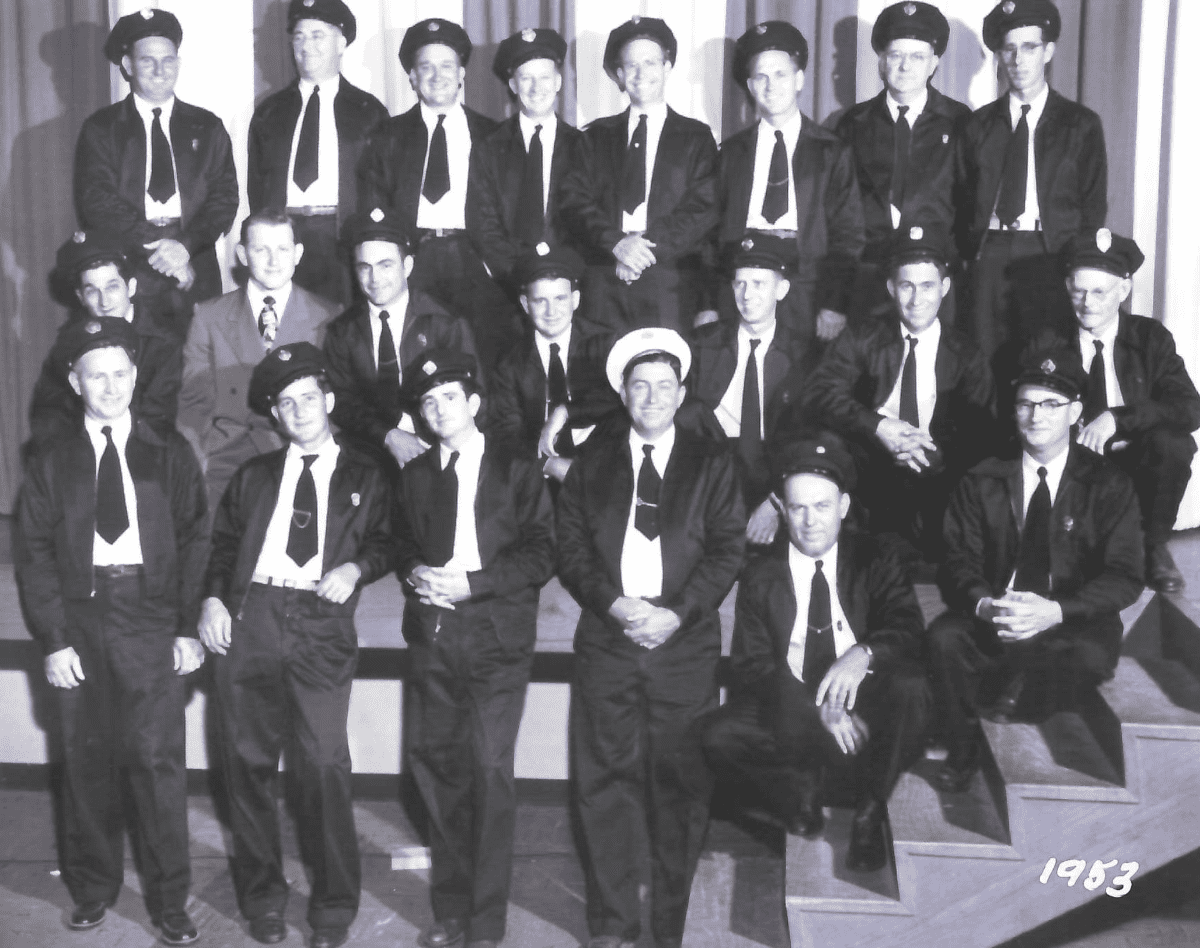

West Columbia Fire Chief Cecil Autry (wearing white hat in center of front row) and Charlie Alexander saved the life of fellow fireman Jack Weems (pictured at left on front row) when Weems, Joe Wisnieski and Abe Jones were swept away in the surf at the beach near Freeport the night of May 22, 1948. Autry and Alexander were successful in getting Weems and Wisnieski back to shore safely, but Jones drowned.

In addition to Abe Jones, Jack Weems and Joe Wisnieski were also swept away but, due to the heroic efforts of Cecil Autry and Charlie Alexander, Weems and Wisnieski were rescued from drowning. The same night Abe Jones drowned another man drowned at Surfside in an unrelated incident. The body of L. Dewitt Peyton Jr. of Bentonia, Mississippi, also a World War II veteran in the U.S. Navy, was found about midnight May 22, 1948, about 2 miles from the jetties. Peyton had been visiting friends in the Freeport area.

Jones’ drowning occurred about 11 p.m. the same night. John Damon and Luby Sorrels of West Columbia patrolled the beach while other members of Jones’ party went for the Coast Guard, The Facts story said. Damon and Sorrels reportedly recovered their friend’s body from the surf and brought Jones ashore where Jim Scott and Howard “Stud” Pangburn administered artificial respiration, along with members of the Coast Guard, for over an hour in an unsuccessful attempt to save Jones’ life.

Cecil Autry was the first fire chief when West Columbia’s volunteer fire department was formed. Autry, Jones, Weems and many of the others in the fishing party that horrible night in 1948 were volunteer fire fighters. John Damon is a former Brazoria County Judge, Jim Scott was a longtime local municipal court judge and a former mayor of West Columbia, and H.O. Pangburn was a longtime city councilman in West Columbia.

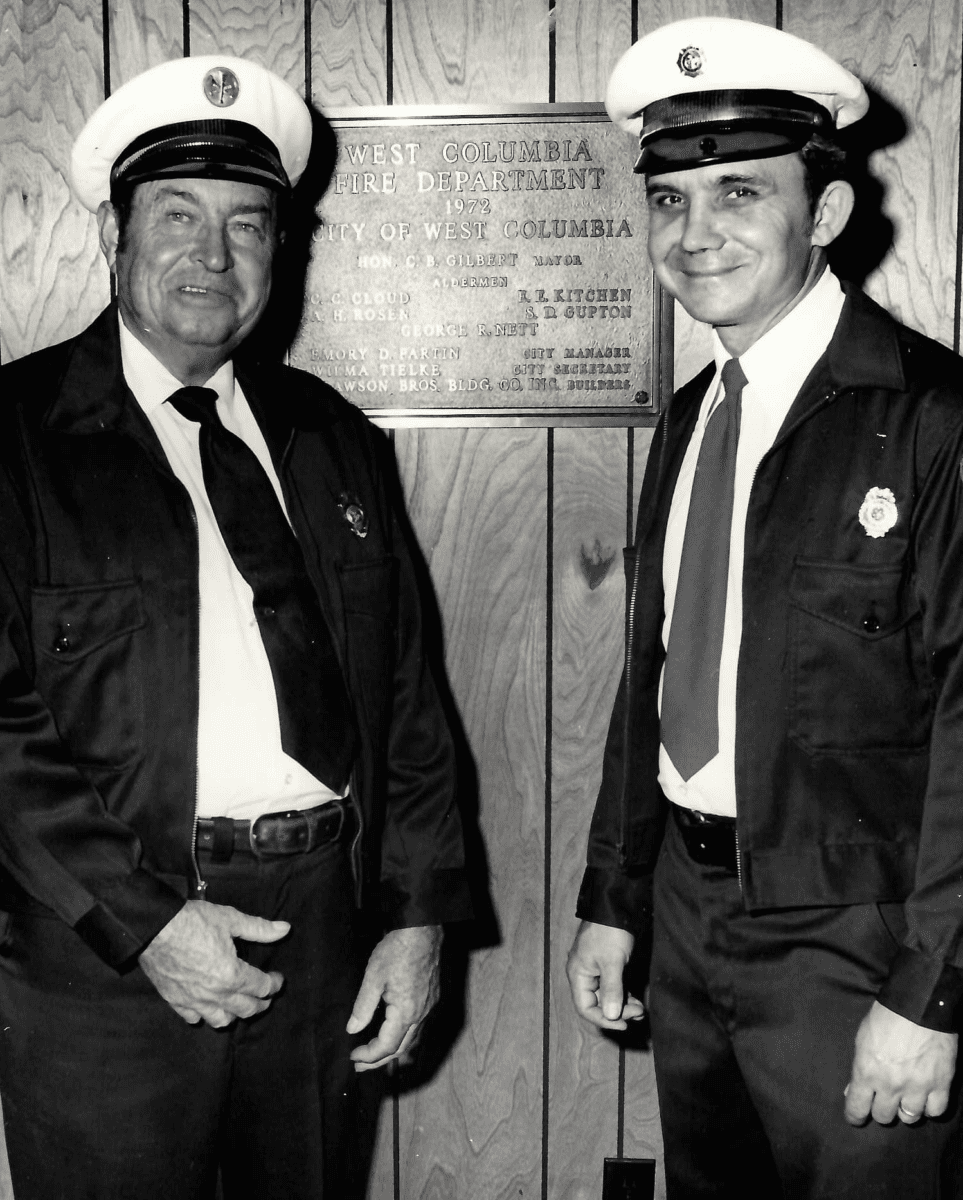

West Columbia Fire Chiefs Cecil Autry, left, and Eugene Fink posed for photos at the open house of the new fire station in 1972. Chief Autry and Charlie Alexander succeeded in saving fellow volunteer firemen Jack Weems and Joe Wisnieski from drowning in May 1948 at Surfside.

Jones was survived by his wife, Josephine, and their 3-year-old son, Danny Boyd Jones. Josephine Jones was the sister of Cecil Autry’s wife, Charlotte, so the W.C. fire chief was devastated that he was unable to save his brother-in-law from drowning at the beach.

My mother’s brother, Howard Giesler, was equally devastated when his friend and fishing companion drowned in the Brazos River near East Columbia on June 15, 1947. Giesler and Jessie Courtney Hudgins Jr. jumped from a boat in the Brazos when the boat motor caught fire. Giesler, who would later serve as an Army medic in the Korean War, swam safely to shore.

Hudgins, a veteran of the U.S. Navy, was wearing cowboy boots that filled with river water, impeding his struggles to reach the bank. Howard Giesler, known to his family and friends as “Hob,” made several unsuccessful attempts to save his friend. The West Columbia Fire Department and Brazoria County law officials searched the river for Hudgins’ body. Local insurance salesman Ed Williams was in a boat when the grappling hook he was using eventually caught hold of Hudgins’ clothing and his lifeless body was pulled into the boat.

Longtime East Columbia commercial fisherman Howard Giesler is pictured with a large alligator taken from the Brazos River in the 1940s.

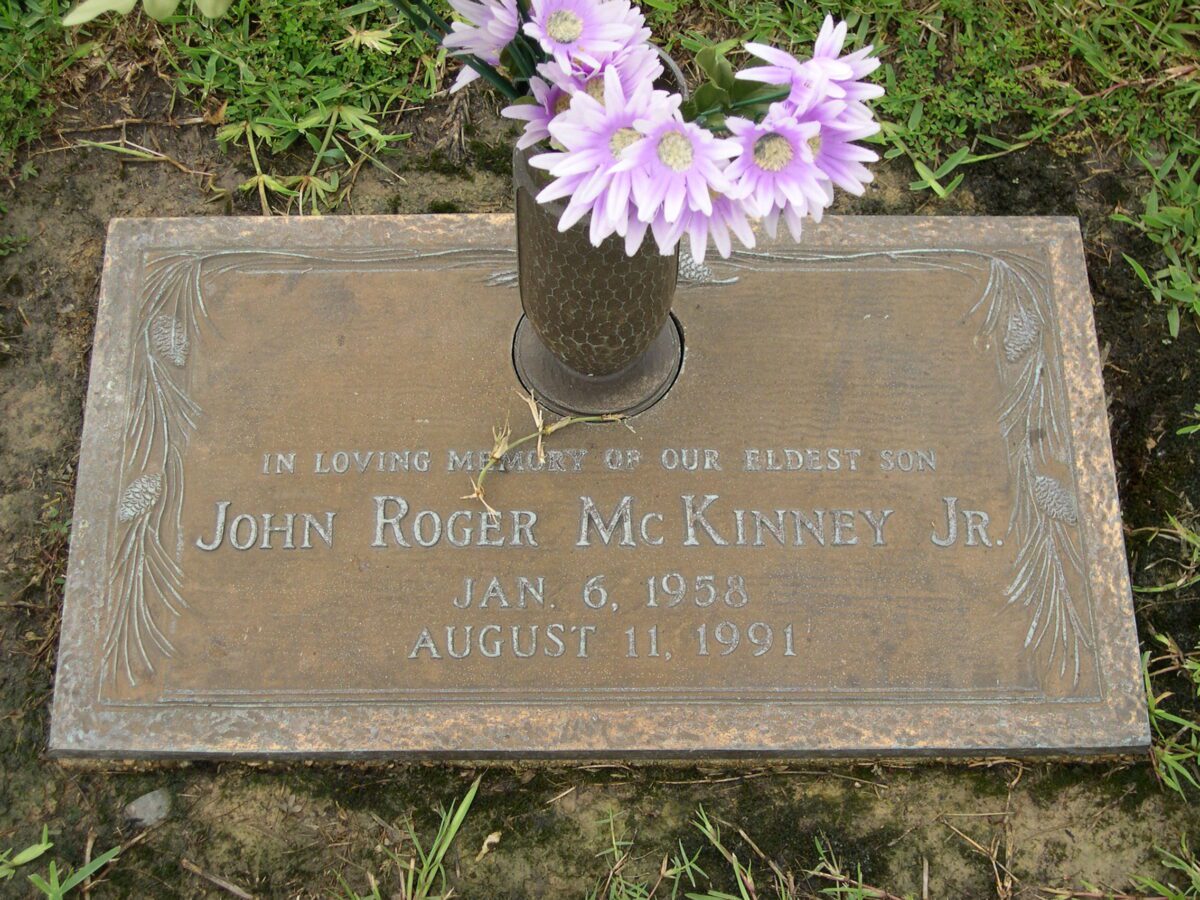

The body of John McKinney, a 1976 graduate of Columbia High School and a good friend of mine since we attended Bible school classes as small children at the Methodist church in West Columbia, was pulled from the Brazos River as well on August 11, 1991. John was only 33.

Local media coverage was thorough on the drowning deaths of Jessie Hudgins, Abe Jones, J.D. Amboree, Steve Denson and John McKinney, whose death was ruled a homicide. He may have already been dead before his killers placed McKinney’s body in the Brazos.

Steve Denson, my fellow 1975 graduate of Columbia High, drowned in the San Bernard River outside West Columbia on April 13, 2004. His death was ruled an accidental drowning although it occurred under suspicious circumstances. Steve Denson and John McKinney are buried at Cedar Lawn Haven of Rest Cemetery in West Columbia, John D. Amboree Jr. was laid to rest at Paradise Cemetery in West Columbia, while Abe Jones and Jessie Hudgins Jr. are interred at Columbia Cemetery where three members of the same family who all drowned during a family outing are also buried.

On April 21, 1929, Gideon Val Lincecum, his wife, Sabra Elizabeth “Bettie” Lincecum, and their niece, Daisy Lynch, were caught in an undertow and drowned at the mouth of the San Bernard River. Two other West Columbians who were swimming with the Lincecums and their niece, Daisy Lynch’s husband, Jack Lynch, and Daisy’s mother, a Mrs. Brown, managed to fight their way back to the shore and avoid drowning.

A joint funeral for the three drowning victims from the same family was held in West Columbia on April 22, 1929. Gideon Lincecum and his wife Bettie were both 33 while their niece Daisy Lynch was only 20. They all drowned on San Jacinto Day in 1929.

The most famous person to die from drowning near West Columbia was Constantine W. Buckley, former Speaker of the Texas House of Representatives, who drowned in the Brazos River at East Columbia on December 19, 1865, at the age of 50.

Born in Surry County, North Carolina, in 1815, Buckley moved to Houston from Columbus, Georgia, in 1838. Texas Governor James Pinckney Henderson appointed him a district judge in 1847. Buckley resigned in 1854 to resume private practice and was elected to the House of Representatives from Richmond, Texas, in 1857.

He represented Austin and Fort Bend counties in the seventh, eighth and ninth Legislatures. There is a state historical marker on the Fort Bend County courthouse lawn honoring Constantine Buckley’s memory in Richmond.

The Brazos River also claimed the life of James Landrum, the father of my childhood friend Rickey Landrum who also graduated from Columbia High School in 1975. The Landrums lived on the banks of the Brazos in East Columbia where James Landrum spent countless hours running his boat up and down the river fishing. He was missing for several days before the body of James Landrum was discovered in the Brazos.