![]()

By Tracy Gupton

When her life ended in 1940 on this day 83 years ago, Annette Finnigan was the age I am now. She was in her 66th year when cancer cut short the life of the renowned philanthropist, suffragette and patron of the arts.

Annette was born in West Columbia, Texas, in 1873, the daughter of John Finnigan and Katherine McRedmond. Her father was a successful animal hide merchant in Brazoria County. Although she was born here, it is doubtful Annette Finnigan had many memories of living in the town that was the first capitol of the Republic of Texas.

John and Katherine moved to Houston when Annette was only three years old, according to Sherilyn Brandenstein’s 1995 biography of Finnigan on the Texas State Historical Association website [https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/finnigan-annette]. She and her two sisters, Katherine and Elizabeth, attended public schools in Houston until the family relocated to New Hampshire in 1888 when their father oversaw the management of the John Finnigan Hide Company business in New York City.

The West Columbia-born Annette Finnigan, “Nettie” to her family and close friends, joined her father’s business enterprise after graduating from first Tilden Seminary in West Lebanon, New Hampshire, then Wellesley College, a private women’s liberal arts college in Massachusetts, in 1894. At Wellesley Annette studied languages, rhetoric, art history and the sciences and was involved in the art society and the Wellesley Bicycle Club, according to Betty Trapp Chapman who authored the magazine article “Annette Finnigan: Building an Enlightened Community” in the Spring 2012 edition of Houston History magazine [https://houstonhistorymagazine.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/finnigan.pdf].

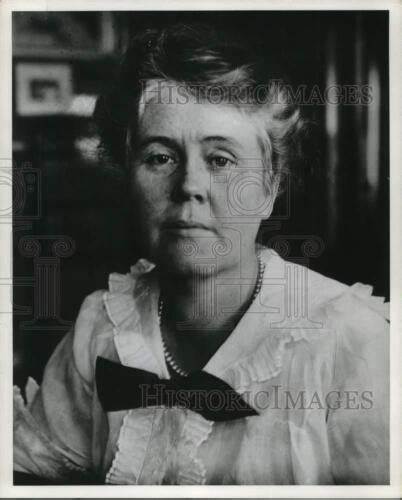

This 1937 portrait of Annette Finnigan was done by John Wells. She died of cancer 3 years later.

Wellesley’s unique policy of employing an all-female faculty provided strong role models for young students like Annette Finnigan and affirmed the concept of feminine leadership. Class elections and assemblies educated women in organization, leadership, cooperation and articulating their views. Annette’s introduction to suffrage occurred during her freshman year at Wellesley when she heard an eminent suffragist speak in Boston. By Annette’s senior year, some 500 Wellesley students and professors declared themselves in favor of woman suffrage.

Even though she was young and inexperienced, Annette was left in charge by her father of his animal hide business when he was away from New York City on travels. The John Finnigan Hide Company had offices in 23 Texas locations when it was thriving. Annette also enjoyed travel, both in America and abroad, and found time to study philosophy at Columbia University in New York City when back at home.

She moved back to Houston with her parents in 1903 and immersed herself in the cultural movement that was just getting off the ground in the early days of the 20th century in the city named for the Republic of Texas’s first president, General Sam Houston. Houston became the capitol city of the Republic of Texas in 1837 after the young republic’s governing body relocated there from Columbia, prior to the Texas capitol being relocated to Austin, named after the “Father of Texas,” Stephen F. Austin who died in Columbia in December of 1836.

A young “Nettie” Finnigan photographed when she was a resident of the New York City area

Annette Finnigan was a founding member of the Houston Equal Suffrage League that pushed to get women to serve in more important roles both politically and publicly in Texas’s largest city. “The importance of selecting persons of the highest intelligence, broadest culture and noblest character to guide the education of the city’s children,” is how Annette responded when the Houston Equal Suffrage League’s first effort to get a woman elected to the Houston ISD school board failed in the early 1900s.

“Nettie” Finnigan collaborated with her sisters—Elizabeth Finnigan and Katherine Finnigan Anderson—in launching equal-suffrage leagues in Houston and Galveston in the early 1900s. These were the first 20th century woman suffrage efforts in Texas. Annette Finnigan was the first president of the Texas Woman Suffrage Association from 1904 to 1906. The women’s rights movement simmered on low heat during the years after 1906 when Annette began spending more time in New York City, but in 1913 she returned to Houston and revived the suffrage league there.

In January 1915 she moved to Austin to lobby the legislature for a constitutional amendment aimed at authorizing woman suffrage. It wasn’t until June 4, 1919, that the 19th Amendment was passed by the U.S. Congress. Victory for women took decades of agitation and protest led by such stalwarts of the movement like Annette, Katherine and Elizabeth Finnigan who had family roots in West Columbia.

Annette was serving as president of the Hotel Brazos in Houston when her father passed away in 1909. With John Finnigan out of the picture, his daughter Annette assumed control over his estate as John specified in his will. She took control of the John Finnigan Hide Company, the Houston Packing Company and the Hotel Brazos Company.

When she was president of the Texas Woman Suffrage Association the organization’s headquarters were at the Hotel Brazos which was located across from the Southern Pacific railroad station between Washington Street and Buffalo Bayou in Houston. Famous guests of the Hotel Brazos, which was demolished in 1931 to make room for construction of a larger Southern Pacific terminal, included Presidents William Howard Taft and Theodore Roosevelt. Under her leadership the number of Texas TWSA clubs increased from only eight to 21 and the Lone Star State’s voices crying out for giving women the right to vote became louder and louder.

Annette Finnigan managed The Hotel Brazos in Houston prior to World War I while the headquarters for the Texas Woman Suffrage Association were housed in her hotel. “Her role as a successful businesswoman proved enlightening to a community, which heretofore was dominated by male business leaders.”

She also headed the Women’s Political Union and the Texas Woman Suffrage Association in Houston while leading the push to pass an amendment giving women the right to vote. By the time Congress ratified the 19th Amendment on August 18, 1920, officially granting women in America the right to vote, Annette Finnigan had to use her left hand to cast a ballot for the first time in her life.

As the women’s suffrage movement gained momentum under her leadership, Annette suffered a serious stroke in 1916 which permanently debilitated her right arm and required her to use a cane for the remainder of her life. Her partial paralysis also led to her resigning as president of the Texas Woman Suffrage Association and ended her active role as a suffragist.

But she found other worthwhile endeavors in her remaining years. Annette was one of the founders of the Houston Public Library, which opened in 1929. Like her father, who had endowed the Houston Carnegie Library fund, Annette Finnigan provided the Houston Library’s first and largest grant. She was a passionate book collector, collecting many rare books including a copy of a book by Terence, which at the time was only one of two known in the world. She donated early Texas books and maps to the Houston Public Library and conducted research in Europe to collect illuminated manuscripts and 16th century literary classics for the library in Houston.

Annette Finnigan also donated over 300 objects of great importance to the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, many of which are still on display at the museum at 1001 Bissonnet Street in Houston. Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts incorporated in 1925.

George A. Hill Jr., who was president of the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston during Annette’s lifetime, said “The knowledge with which she collects and the spirit in which her presentations are made are the most interesting events in the life of the museum. She is a connoisseur of art and due to her forethought there are many objects in the museum that might otherwise have been seen in the large museums of Europe.”

Annette Finnigan, born in West Columbia, Texas, in 1873, died in New York City in 1940

She died of cancer on July 17, 1940, in Memorial Hospital in New York City, on this day 83 years ago. Her cremated remains were sent to Houston for burial in Glenwood Cemetery.

Following her death, Annette left provisions in her will to establish the Annette Finnigan Endowment Fund for the Houston Public Library, left large amounts of money to the American Foundation for the Blind and the American Commission for Mental Hygiene, and she established a $25,000 grant to Wellesley College, her alma mater.

Annette Finnigan’s contributions to her hometown of Houston reached beyond her artistic and literary gifts. Her long-standing altruism led her in 1939, one year before her death, to donate 18 acres for use as a park for Houston’s black citizens. Realizing that the segregated city obviously lacked such recreational facilities, Sherilyn Brandenstein wrote in her Texas State Historical Association story, “Finnigan sought to remedy this and requested that the park be named for her father. Today John Finnigan Park is a center of community activity for Fifth Ward Houstonians.”

It was stated in her obituary in The Houston Post that Annette Finnigan was “one who served faithfully many noble causes and left her home city and her country better because of her life.”

A very interesting and informative article about a woman who enhanced the culture of our area of Texas.